Innovations in MWD/LWD and drill pipe technologies address key operator concerns and needs, put previously impossible wells into reach

By Linda Hsieh, assistant managing editor

Operators ask for a lot in their measurement-while-drilling (MWD) and logging-while-drilling (LWD) tools. And why shouldn’t they, considering the sizable chunks these services can chew off of a budget?

The growing number of directional, extended-reach and highly deviated wells means that MWD/LWD technologies are often indispensable – certainly if you want to have efficient wellbore placement. At the same time, drilling environments are increasingly harsher and putting extreme stresses on downhole tools – which means higher risks for failure.

For their part, the service sector has made important breakthroughs and set impressive records, and continue to work on trouble spots like reliability and the ever-elusive look-ahead capability. Drilling Contractor surveyed five major oil companies, then took their challenges and criticisms (anonymously) to two oilfield service providers. Below are some of the significant issues discussed.

BHA vibration

Downhole shock and vibration continue to be problematic, and the challenge is exacerbated by the increase in number of extended-reach and ultra-deepwater wells. One operator noted the need for accurate, high-frequency downhole vibration and bending monitoring tools in real time, integrated with all MWD tools. Another cited vibration as a cause in reducing his drilling penetration rates. It can also make the borehole twisted, causing “false” images to LWD tools, he said.

Jim Wilson, principal global champion for MWD/LWD for Halliburton’s Sperry Drilling Services, offered a couple of solutions they’re developing. First, his company is incorporating the DDS-R (Drillstring Dynamics Sensor) into their LWD tools, which “helps us understand the shocks and vibrations we’re experiencing.” When drillstring vibration exceeds pre-set thresholds, real-time alarm information will be transmitted to the surface, allowing for corrective action.

Separately, the company plans to launch the WTB sensor later this year. This tool will help drillers see three critical downhole phenomena – weight on bit, torque on bit and bend on bit – in real time so that drilling parameters can be optimized.

Paul Radzinski, global marketing manager for Weatherford Drilling Services, offered this take instead: Prevention is better than a cure. Pre-well planning is absolutely critical to efficiently preventing damaging BHA vibration.

“Through pre-well planning, we can model very accurately the BHA and proper stabilizers placement. We can tell an operator where the critical harmonics are and how to avoid BHA vibration and its damaging effects.”

“It’s so much better to prevent yourself from getting into the situation than trying to build something to survive the worst-case scenarios,” he said. “Rather than trying to build a car that won’t get damaged when it hits a tree, just try and avoid the tree.”

High pressures, high temperatures

Operators seem to agree that, for most wells, current MWD/LWD systems can handle the upper ranges of temperatures and pressures they see. However, they also say that cutting-edge HPHT developments have created a need for further improvement. One operator urged that temperature/pressure limits be upscaled to 200°C (400°F) and 35,000 psi.

“We have in our portfolio several prospects beyond 177°C,” another said. In one case, high-pressure conditions made it mandatory for the operator to take up development of “basic downhole tools” with partners and a major service company. “It is surprising that the (service companies) are not prone to developing such tools … despite the worldwide deeply buried reservoirs potential,” he added.

Service companies, however, say they are in fact putting in R&D dollars into designing and improving HPHT tools. Sperry is in the progress of working towards 35,000-psi tools, Mr Wilson said, and they plan to selectively upgrade LWD tools to 175°C and 30,000 psi, as dictated by market requirements.

Weatherford says it is proud of its achievements in HPHT wells around the world, noting that they hold the LWD world record for highest temperature (193°C, North Sea, 2005) and recently set a high-pressure record in the Gulf of Mexico last summer by going to 34,100 psi with a full LWD. “I have confidence that any well with a pressure approximating 30,000 psi, we will probably have an excellent chance of success,” Mr Radzinski said.

On the temperature side, the company noted that it will commercialize its 165°C-capable Shock Wave LWD Sonic tool later this year. It also recently provided LWD equipment able to work at 180°C and 30,000 psi in an HPHT field in northern Italy, allowing the operator to drill a 5 ¾-in. sidetrack well to access previously bypassed reserves. (See detailed case study, Page 22.)

Perhaps you might say that these advances are incremental changes rather than the major upgrades that operators seem to be requesting. Yet service companies point to the overall niche status of such high-temperature and high-pressure wells – which makes this kind of R&D a costly and potentially risky task.

“The overall extreme-HT market is small, yet the engineering cost to meet this challenge is huge. To just go another 20 degrees would be a very large effort,” Mr Radzinski said.

Fluid sampling

One capability that operators have wanted for years is a fluid sampling feature to complement pressure-while-drilling or testing-while-drilling tools. Now, Sperry says they may be ready to fill that gap with what could be a “game-changing” technology, according to Mr Wilson.

The InSite GeoTap IDS (identification/sampling) builds on the GeoTap formation pressure testing tool, available since 2002, to allow fluid identification and sampling as the well is being drilled, while obtaining pressure measurements at the same time. The new system will support real-time identification of reservoir fluid properties such as density, viscosity and conductivity, as well as enable timely downhole capture and surface recovery of multiple samples of uncontaminated formation fluids.”

“Customers spend millions of dollars obtaining these data on wireline after the well has been drilled. With this tool, you’re able to do it in the drillstring BHA,” Mr Wilson said. Within hours, they could get a formation sample that’s 95% clean for further analysis.

The demand for this technology has been huge, and Mr Wilson recalls operators already asking ‘Can you take samples?’ on the day the original GeoTap was introduced a few years ago. “We have been working on the technologies, building on and leveraging off of the GeoTap formation pressure testing tool.”

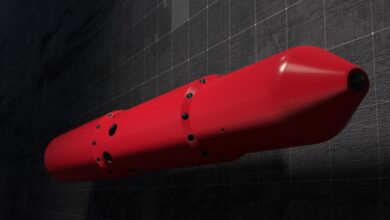

The result is the GeoTap IDS – “probably the most complex tool that’s ever been built in the LWD arena,” said Mr Wilson. The tool is currently undergoing further tests and should go into the ground for commercial field testing in Q2 or Q3 of 2009, depending on the success of initial tests, he said. (See Page 28 for more information about two other new InSite tools coming out in 2009 – a litho density neutron tool and a multi-well geosteering service.)

Reliability

“The biggest value impact from LWD/MWD/DD is to get it right the first time,” one operator noted. Yet tool reliability issues continue to eat away at this value – whether because of component failures, QA/QC problems or human error.

Service companies appear to agree on this point and emphasize that they understand the importance of reliability.

“The No.1 buying criteria is absolutely reliability. You can have everything working great, but if you have one part fail twice as often as your competition, you won’t get the contract. Coming out of the hole is very expensive – it could be a significant portion of the entire rig cost,” Mr Radzinski said.

Service companies say they continuously take on all sorts of destructive testing, vibration testing, pressure testing, etc, to ruggedize and improve their tools.

“We’re reducing connections, reducing the number of electronic boards in there, including redundancy where possible and taking advantage of the advances in the computer/electronics industry to have smaller LWD tools that are less impacted by the huge shocks and vibrations they experience downhole,” Mr Wilson said.

Another way they’re tackling reliability is through competent training, added Mr Radzinski, who attributes one-third of all tool failures to human error. “30% is a big segment of total failures, so training and hiring good, competent people is something we’ve been focusing on.”

The lack of an industry standard for measuring reliability also makes it difficult to talk about the issues, he continued. “For airlines, there’s a government standard for on-time arrival, so you can see who’s the best. But in our industry, there is no common standard for reliability.”

For now, looks like operators may just have to remember that, sometimes, the value of the MWD/LWD service is simply being able to obtain these downhole data in real time.

Looking ahead of the bit

The capability to see ahead of the drill bit – especially in vertical, exploration wells – has been a long-sought-after yet elusive goal for the drilling industry. After decades of research, there are still few seismic-while-drilling (SWD) systems on the market, and acceptance among operators remains low.

One operator noted that SWD systems have not been accepted at his company “maybe because the first tests conducted did not work out satisfactorily.”

Another elaborated more, saying that “90% of current (SWD and vertical seismic profile/VSP) techniques are just used for a time-depth calibration. The reason is simple: The look-ahead is still difficult and just obtained today in some VSP for vertical wells. … We have today no solution fitting all our expectations. The gap is rig time impact, deviation of the well, continuous and real-time survey acquisition and processing, real time with look-ahead feature, HPHT.”

Mr Radzinski acknowledged these concerns, noting that SWD technologies “just seem to have difficulty gaining traction.” “The perfect tool would be right at the bit or in front of the bit to directly measure the pore pressure, and that sensor does not yet exist,” he continued.

Michael Bittar, director of formation evaluation technology for Halliburton’s drilling and evaluation division, agreed that look-ahead capabilities need more work. “We’re hoping to have the breakthrough. It is an extremely difficult problem to focus the sonic or electromagnetic signal ahead of the bit. … We all understand the importance of look-ahead, and I think it’s something the whole industry will work on, but we have to understand the difficulties.”

Cost vs benefits

The issue of cost always seems to be a rather difficult one to achieve consensus and agreement on between operator and service company. One side believes that costs for LWD/MWD have risen to “prohibitive” levels. In combination with smaller volumes per well in mature basins, the reliability issues mentioned earlier, and companies’ risk aversion tendencies, “there are projects/wells where the ‘value for money’ balance tips to the side of no LWD/MWD at all,” one operator said.

On the other side, service companies point to the tremendous costs they must undertake in order to build these highly sophisticated and complex tools.

Moreover, LWD/MWD costs must be considered in terms of the total rig cost, Mr Radzinski said. “If the rig cost is $8,000/day, there’s no economic reason to run LWD. An operator can’t afford it. If you’re running a $700,000/day rig, you wouldn’t even think about it – you run it. And if it’s a $70,000/day rig, you have to look at the cost vs benefits. Still, a lot of wells need a basic LWD service to properly place the wellbore through geosteering. Sometimes you just can’t drill the objective properly without it.”