Global LNG market boosts hope for better natural gas future

No direct impact yet, but growing export expectations could encourage North American gas drilling

By Joanne Liou, editorial coordinator

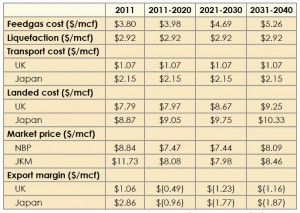

Reviews of the 2012 drilling year reflect the continuation of low North American natural gas prices of $2.50/Mcf to $3.50/Mcf, which is causing a shift from gas drilling to oil drilling. However, on the other end of the forecast spectrum, the prospects of an emerging and growing liquefied natural gas (LNG) export market coupled with increased domestic gas demand could boost gas-directed drilling across North America. Bill Gwozd, senior vice president, gas services, Ziff Energy Group, believes the growth of LNG export markets around the world are encouraging additional drilling activity across North America.

Another unconventional strategy is the pursuit of gas-to-

liquid (GTL) technology that converts natural gas to liquid form, increasing opportunities to utilize the resource and therefore accelerate additional gas drilling. Companies have the ability to take surplus natural gas and convert it to diesel by using GTL, Mr Gwozd said. The process is economical, he said, proven and under way in several plants worldwide. Additional plants have been proposed for Louisiana and near Edmonton in northern Canada.

“The benefit here is the low price of natural gas as a feedstock for the GTL process, and that diesel is marketed at a high price that is comparable to oil prices.”

Although LNG may not be directly impacting the North American drilling activity yet, companies might consider the potential revenues that could be realized once US LNG facilities come online. “If (LNG) has done anything, it has slowed drilling in places like the Haynesville because the fear has been that a lot of these companies would pass their peak production before a facility was opened,” James Wicklund, managing director at Credit Suisse, explained. “They would have produced the bulk of their natural gas before a better market came along.”

Compounding that fear with already low natural gas prices, some companies are drilling just enough to hold acreage while hoping for a better market in the future, he noted.

Low natural gas prices remain a concern for companies with operations in Canada as well. EOG Resources and Apache Corp, among other companies, are looking to build an LNG facility in western British Columbia, where the Horne River formation would supply the facility with natural gas for liquefaction for export to Japan and other areas in the eastern hemisphere. However, natural gas prices have dropped so dramatically that the economic break-even of the play is estimated to be $6 to $7, Mr Wicklund said. Companies are hoping that by the time the LNG facilities come online, natural gas prices will have risen enough to profitable, he added.

LNG facilities

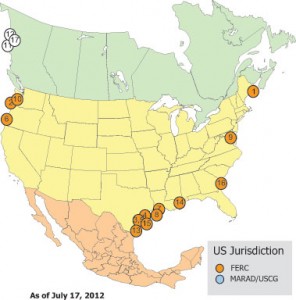

The surge in shale gas production, aided by hydraulic fracturing technologies, has rerouted North America’s energy road map. Nearly a decade ago, the US began to invest in LNG terminals with the intention of importing the precious resource. Fast forward to present day, and many of those facilities sit idle with proposals to retrofit them for the exact opposite purpose: to export LNG. North America has 11 LNG terminals, including one in Puerto Rico, according to the US Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC).

“The plan was for the US to become a major importer, but then shale happened and sort of turned the card upside down,” said Kenneth Medlock III, an adjunct professor and lecturer of economics and senior director at Rice University’s Center for Energy Studies at the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy. “Shale happened as we were building a lot of import

infrastructure, and it all sits idle now, which is where all this interest to turn those facilities around comes from because you want to make use of idle capital.”

LNG, the liquid form of natural gas, predominantly as methane, occupies about 600 times less space than natural gas when chilled to about -260°F (-162°C). The properties of LNG allow it to be stored in specially designed tanks and transported to distant markets, where LNG can be regasified and utilized as a source of energy. “With countries like Japan, Italy and Germany turning against nuclear to generate electricity and the world being increasingly concerned about pollution, natural gas demand is expected to grow for the foreseeable future globally,” Mr Wicklund stated.

LNG markets

The growing global LNG market reached 241.5 million tons in 2011, with a sharp increase from Japan by 8.2 million tons, according to the International Gas Union’s 2011 LNG Report.

With Japan and South Korea being the main consumers, “the market right now is not that large; you have a number of different exporting countries meeting that demand,” said Mr Medlock, who is also a James A Baker III and Susan G Baker fellow in energy and resource economics at Rice University. However, the market is bound to change as more markets, such as China and India, position themselves to import more LNG and more exporting countries enter the market or expand demand.

Qatar has emerged as one of the top LNG exporters on the international level within the last few years, exporting about 77 million tons of LNG in 2011. Other Middle Eastern countries exporting LNG include Oman, United Arab Emirates and Yemen. Out of Africa, Algeria, Nigeria and Egypt are exporting, and there has been discussion about countries such as Equatorial Guinea and Angola, Mr Medlock noted. Further into the eastern hemisphere, Russia is exporting out of Sakhalin Island, and Papua New Guinea will be on the map soon with the PNG LNG project with ExxonMobil scheduled to begin its first LNG deliveries in 2014.

Projects scheduled to come online in Australia over the next few years are expected to put the country on par with Qatar in terms of export volumes as well, Mr Medlock said. “In Australia alone, you see a near doubling of export volumes in the next three to four years because of projects that are already under construction.”

Chevron Australia began construction of the $29 billion Wheatstone Project off the Pilbara coast of Western Australia in late 2011. The project is expected to begin LNG production in 2016 and will have two LNG trains with a combined capacity of 8.9 million tons per year. The Gorgon Project, also led by Chevron Australia on Barrow Island, is scheduled to begin production in 2014. The Gorgon Project is expected to produce 15 million tons per year.

Off the northwest coast of Australia in the Browse Basin, Shell’s floating LNG project is expected to begin production in 2017 and will produce 3.6 million tons per year.

In North America, Canada’s west coast is most likely to take the lead in LNG exports, given lower prices and the location, Mr Gwozd explained. “The price of natural gas in Canada is cheaper; for example, today Henry Hub is about $3 to $3.50/Mcf, while Western Canada’s price is under $3.00/Mcf,” he said. “That means that the Canadian natural gas feed stock is cheaper to send overseas and thus a higher profitability.”

Distance is another factor: The projects on the west coast of Canada are closer than the US projects in the Gulf of Mexico.

Canada consumes about half as much natural gas it produces, Mr Gwozd said, which means opportunities to sell the other half to markets like Asia, where natural gas prices range between $13 to $15. Companies such as Apache, EOG, Encana, Shell and BG are establishing an LNG export presence in Canada. Mr Gwozd likened the activity to a square dance, where in Western Canada, joint ventures are attracting some Asian players, such as Kogas, Mitsubishi, Petronas and Intex.

“The square dance partners will be learning the Canadian way of doing business and will try to get involved in this square dance process and bring large sums of money to make these projects go ahead,” he explained. “Because there are so many more players looking at Canada as a whole, it also reinforces the economics that Canada is the place you want to be.”

Ironically, while the US is home to massive natural gas production relative many other countries, only one LNG project is currently licensed and under development. Cheniere Energy Partners received authorization from the US Federal Energy Regulatory Commission in April to install liquefaction services at the Sabine Pass LNG receiving terminal in Cameron Parish, La., which will essentially transform it into a bi-directional facility capable of liquefying and exporting natural gas in addition to importing and regasifying LNG.

Although some analysts are skeptical of when operations will come online, Cheniere Energy has said it aims to commence operations in 2015. The planned export total is 2 Bcf/day.

There are several applications for licenses to export LNG – ranging from the Dominion-led Cove Point project in Maryland to Jordan Cove in Oregon – totaling more than 17 Bcf/day, Mr Medlock said.

Challenges to export

The development of an LNG export market in the US is not without challenges from political and environmental opposition, infrastructure, and commercial uncertainties. “There are a number of plans and permits that have been applied for, but it’s expected that there probably won’t be any approved for a couple of years,” Mr Wicklund explained. “When Cheniere was trying to get their LNG facility permitted, the environmentalists and others fought it, saying, ‘Instead of shipping our precious natural gas overseas, we should be using it here.’”

Infrastructure is also lacking. The existing terminals were constructed to import LNG, not export. “If infrastructure existed, we’d be exporting as much as we could because the prices in the US relative to the price in Asia reflect differentials in the $12 to $14 range. That’s more than enough to pay for a trade,” Mr Medlock noted.

Although the current price differential between the US and other markets is in favor of exports, the question is whether the price will remain sufficient to support trade. The costs of liquefying, shipping and regasifying takes a toll on the potential net earnings, and competition could also reduce prices outside the US. “Ultimately, how does contract structure change once you increase liquidity, which will ultimately happen the more players there are in the market,” Mr Medlock stated. “All that is commercial in nature.”

Natural gas vehicles

The potential demand for natural gas for the transportation sector in North America is gaining momentum. “In the near term, the growth won’t be spectacular, but by 2020 in the fleet sector where we feel the near-term prospects are the best, you would have fairly significant demand,” Nina Fahy, associate director, PIRA Energy Group, explained.

Based on PIRA Energy Group’s high case, by 2020, the fleet usage, which generally includes vehicles that are owned by the government or corporations, is estimated to reach 1.5 Bcf/day. By 2030, that usage is forecast to reach 4 Bcf/day. US natural gas consumption will average 69.8 Bcf/day in 2012, an increase of 3.2 Bcf/day from 2011, according to the US Energy Information Administration.

Developing one side of the equation while trying to develop the other side is a conundrum. “You’re trying to create a market for trucks that for the most part are not already built and also create a fueling infrastructure, which those trucks can then get gas from,” Ms Fahy explained. “It becomes a challenge of how you can substantially affect both sides of that equation and have it move in tandem because it really is very interdependent to have both the trucks and the stations built.”

Progress is being made, largely because of private initiatives that target both fueling infrastructure and original equipment manufacturers. LNG truck engine options are limited; however, Cummins Westport is scheduled to release an 11.9-liter LNG engine in 2013 to fill a niche. “At present, there are really only lighter engine options or heavier engine options; this will satisfy a middle ground,” Ms Fahy said.

Her outlook for progress in the NGV market in 2013 is promising, as she expects to see more LNG fueling infrastructure be built for Class-8 vehicles – trucks weighing above 33,000 lbs (14,969 kg), including tractor trailer trucks – and for public transit buses and refuse trucks. Further, she expects that each of the big three US auto manufacturers will have an NGV on the market in 2013.