Ensuring reliability, and proving it

Industry addresses asset integrity through data-driven programs, focus on human factors, enhanced documentation

By Linda Hsieh, Managing Editor with reporting by Jesse Maldonado, Associate Editor

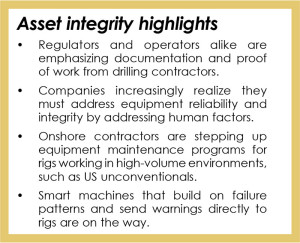

From reliability-centered maintenance programs to integrated sensors to advanced risk modeling, the drilling industry is dedicating more resources than ever to ensuring the integrity of its assets. However, in this post-Macondo world, simply doing the work is oftentimes not enough anymore. We’re now increasingly being asked – by operators as well as regulators – to provide evidence of when the work was done, who did it and if that person was qualified, and how that person conducted the work.

From reliability-centered maintenance programs to integrated sensors to advanced risk modeling, the drilling industry is dedicating more resources than ever to ensuring the integrity of its assets. However, in this post-Macondo world, simply doing the work is oftentimes not enough anymore. We’re now increasingly being asked – by operators as well as regulators – to provide evidence of when the work was done, who did it and if that person was qualified, and how that person conducted the work.

Diamond Offshore, for example, has significantly amped up its efforts around documentation when it comes to equipment maintenance. “There’s a lot more emphasis on contractors doing their work as their company’s management system says they are going to do. Operators want to be able to see maintenance records and proof of certifications. They want to ensure we are doing what we say we are doing and not just pencil-whipping it,” Frank Breland, Manager of Planned Maintenance for Diamond Offshore, said.

provides remote monitoring capabilities and advisory

services for critical assets on rigs, such as engines, top drives, mud pumps and drawworks.

At the same time, increasing equipment complexity is putting stress on what companies require of their personnel. This continues to push the development and adoption of data-driven maintenance processes that incorporate sensor-collected data, understanding of failure modes and real-time monitoring. The drilling industry has historically been skeptical of technologies, like sensors, believing that having more sensors means less reliability. Now, that mindset is changing, Ashe Menon, Director of Asset Management for National Oilwell Varco (NOV), said. “Since we are drilling deeper wells and the equipment is working so much harder, we really need these extra capabilities to identify trouble spots before they fail. This is the way the industry is going.”

Nevertheless, the industry recognizes that no matter how sophisticated the equipment gets, it can’t function without competent people. As more complex systems are used to manage more complex assets and operational objectives, companies are recognizing that they need to focus, too, on the human interface. “It is important to look at how people interpret data,” Pieter van Asten, Business Concepts Manager for Lloyd’s Register Energy – Drilling (LRED), said. “That is very challenging and can be of greater importance than equipment failure because it’s not black and white. There’s a lot of grey in between.”

Reliability-centered maintenance

Back in 2010, Ensco kicked off a more robust reliability-centered maintenance (RCM) program, focusing initially on pipe-handling equipment. “Reliability-centered maintenance is a very methodical way in which we analyze the failure modes of a particular piece of equipment and how we can prevent those failure modes. The ultimate goal is ensuring the integrity of our assets,” Sachin Mehra, Ensco VP of Asset Management, said.

This comprehensive process begins by establishing a multidisciplinary team that includes not just drilling contractor personnel but also the OEM. A five-day session, facilitated by a third-party company, is then held where team members come together to discuss all possible failure methods for a particular piece of equipment and brainstorm solutions for failure prevention. “These sessions don’t have to be five days – they could be three days or eight days, depending on the complexity of the equipment,” Mr Mehra said. Regardless the length of the sessions, a significant amount of information is generated through these discussions, and it could take months to further analyze that information and turn it into action items.

At this point, Mr Mehra stressed, it’s critical that the drilling contractor follows through by implementing those action items on its rigs. “You only get the real benefit of the RCM study if you implement changes in operations and maintenance. Those changes could be many things – an alternate equipment component, a redesign of a component to increase reliability, or perhaps the way that equipment is maintained or operated.”

This means a company must be prepared to make the RCM program a long-term investment where payoff may not be immediate. “Sometimes, in order to see the results of a particular RCM study, it could take a year or more depending on what the equipment is,” Mr Mehra said. Taking the long-term view has paid off for Ensco since the program kicked off just four years ago. One of the first RCM studies Ensco did focused on the bridge racker for the ENSCO 8500 Series rigs. Since that study was done and action items were implemented, the average annual downtime for each 8500 Series bridge racker has been reduced by nearly 95%, Mr Mehra explained.

This result was possible because Ensco knew it could leverage the improvements that came out of one RCM study across all of its 8500 Series rigs – one reason the company picked this particular piece of equipment to study in the first place. “The cost of the RCM was spread over seven rigs, and the benefits we gained have benefitted all seven rigs,” he said.

In 2011, after Ensco added a significant drillship fleet through the Pride International acquisition, Ensco realized it needed to pivot the focus of its RCM efforts to subsea BOPs and, in particular, BOP control systems. An enhanced RCM study, completed in 2012 on this equipment, is being implemented across the company’s drillship fleet. So far, on just three drillships, Ensco has been able to reduce downtime related to this equipment by nearly 70%, Mr Mehra said. The company is aiming for further improvement as it continues to analyze downtime statistics and fine-tune its RCM strategy.

Collaboration with OEMs will be particularly important in that effort, he continued. “Equipment design and quality control is a big issue. If you look at Ensco’s asset integrity philosophy, we want to get to a point where the equipment is designed such that it is inherently reliable,” Mr Mehra said. “The industry is still doing a lot of time-bound interventions on equipment. We want to get to a stage where we do our interventions based on condition, not time, and it all goes down to how the equipment is designed, the built-in reliability of the system and how we maintain it.”

Ensco is working with OEMs on equipment that incorporates vibration monitoring, oil analysis and infrared sensors that alert crews to potential problems before a breakdown occurs. These technologies are being built into new equipment and retrofitted to older equipment, he said. “The whole idea is we don’t have to stop the equipment operation in order to assess and understand the condition of the equipment. We can determine the best time to do maintenance in the safest and most efficient way possible – minimizing downtime by preventing equipment failures before they happen,” Mr Mehra said.

Enhancing the documentation process

With SEMS fully under way in the US Gulf of Mexico, offshore drilling contractors are taking the opportunity to significantly improve its documentation process around maintenance. Providing proof of work – not just doing the work – is something that operators and regulators alike are emphasizing around integrity assurance. “Living in a post-Macondo world, the proof of our work is key,” Diamond Offshore’s Mr Breland said. “It’s the documentation, the certifications and the traceability of maintenance. We have to be able to present that in a format that regulatory surveyor or an operator representative is going to accept… We stress to rig personnel that the documentation is just as important as the actual physical work done on the equipment.”

Aside from pre-contract audits, Mr Breland said, Diamond Offshore may go through six or seven SEMS audits a year for various operators. “SEMS has helped us improve our documentation as a whole because we have to be able to present all sorts of records, not just around maintenance.” Diamond also conducts internal equipment audits on a routine basis as part of its overall maintenance program; findings are categorized and prioritized so they can be addressed in a timely fashion.

In keeping with evolving technologies and more complex equipment systems, Diamond Offshore also is updating its computer-based maintenance system to a live web-based one that provides better tracking of equipment components and individual assets. For example, with the old system, crews may do routine maintenance on three mud pumps, then check off maintenance for three pumps. “Now, we’ll do that procedure, but we will document the maintenance on each pump. This allows for better tracking on a daily basis,” he commented.

Eventually, the company hopes the system will allow its workers to collect enough maintenance data that Diamond can use to analyze mean time between failures tied into parts usage. “We want to see if we may have a piece of equipment that appears to be running right but we’re actually spending $20,000 a year on a $4,000 piece of equipment,” Mr Breland said.

The web-based maintenance system has been installed on approximately 70% of Diamond’s fleet so far. Particularly on the company’s newer deepwater units, the system has been critical for ensuring integrity due to the number and complexity of equipment onboard. Top drives, BOPs, dynamic positioning, thrusters and mud pumps are key focus areas, he said, because failure could put the rig on downtime immediately and could lead to major safety incidents. “A failure in your DP system can lead to a well control event in the blink of an eye. We put more emphasis on those safety-critical systems.”

Mr Breland also believes that condition-based monitoring (CBM) with warning systems could help to ensure integrity of safety-critical, big-capital items – but he would like to see more of those CBM systems built into the equipment during the manufacturing process. “It would be much better – and it’s already starting to happen – that the OEMs are building these tools into the equipment. It makes for a much cleaner installation.”

Real-time monitoring services offered by OEMs also can help with integrity issues, but oftentimes they’re dogged by the same people shortage as the contractors are, he said. “Just like drilling contractors, they struggle to maintain personnel. At times it’s helpful, but other times it can be trying because there’s only one person who is an expert on the equipment and maybe he’s not available.”

Mr Breland notes that Diamond Offshore is now beginning its own remote-monitoring efforts, aided by the advanced monitoring capabilities of new-generation rigs. “We’re starting to implement a system that will assist us with software management. Basically, we’ll build a password-protected software library for each rig, and the guys offshore will be able to use this software for diagnostic purposes. We’ll be able to tell when they logged into the system and checked the software and if they needed to make any changes. We will have an MOC process in place, but this is where we are headed.”

Addressing equipment reliability through human factors

The drilling intensity of onshore operations, particularly in North American unconventional plays, has soared in recent years. More wells are being drilled in the same amount of time, and there’s little chance for rest in between wells due to improved rig mobility. “In the Eagle Ford, wells that three years ago took 25 to 30 days to drill are taking 10-11 days or even shorter,” Grant Hunter, Senior VP of US Operations for Precision Drilling, said. “In the shallower side of the Eagle Ford in Maverick and Dimmit counties, where the wells are approximately 15,000- to 15,200-ft measured depth, we’re running two strings of pipe in seven days. The blocks go up and down the same number of times as they did before in 22 days. Everything is condensed. Of course, we’re going to wear our equipment and rigs faster.”

Ensuring asset integrity in this type of high-volume environment means the company must prioritize planning and ensuring sufficient maintenance time is scheduled in, Mr Hunter said. “Everything is pushed hard, 24/7, 365 days a year. We track hours and days on all equipment and service them according to a strict internal equipment maintenance practice,” he explained. Precision uses the SAP management system, which the company has set up to pull rig data directly from the IADC daily drilling reports.

“Tracking time and usage is a big part of our maintenance program, but we are also looking at our rigs all the time,” he continued. “For example, we continuously test lubricants like hydraulic fluids and our engine oils. Our service technicians also get data coming in from the field so they can proactively look for any potential issues.”

Critical components such as overhead and pressure-control equipment do get more attention than others when it comes to ensuring asset integrity, Mr Hunter said. In particular, reliability of the top drive remains a challenge. “We’re working with a couple of service companies to measure vibration through the drill string and at the bit. Unless there’s a mechanical issue with the top drive, that’s where most of the vibration will come from. We’re still in the early stages of this project, but I can tell you, we’re trying to pinpoint the root causes of our top drive issues and figure out what we can do.”

Precision also recognizes that equipment failures are often not mechanical, and the company is tackling the reliability issue from a human factors perspective. “It would be simple if I could say that OEMs are building bad top drives, but that’s not necessarily the case. Aside from the quickness of the wells being drilled now, I would say that human errors play a large role in equipment failures,” Mr Hunter said. Particularly as AC rigs continue to drive the US newbuild market, he said, both rig crews and service technicians are dealing with much more technologically complex equipment.

“Having enough competent people to work on equipment is a big challenge, both for OEMs and contractors,” he said. “This is part of the reason we built our training and tech center in Houston back in 2010.” The 45,000-sq-ft facility houses nearly 40 technicians and shops that manage the maintenance and full life cycle of Precision’s assets. The company also runs a range of competency-based training – including safety, technical and leadership courses – through this facility. A total of 1,400 people went through training here in 2013, and that number is expected to increase significantly this year.

“We train on different levels of technical skills for different job positions, but at every level we make sure the training itself is engaging,” Steve James, VP of Field Training & Development for the Houston Technical Support Center, said. “In our sessions, we run them through exercises where they’re almost teaching each other. We’re just there to facilitate the discussion.” The company tries to build in at least 50% of interactive content into each course. Half of a top drive class, for example, is spent in the shop where students do hands-on work.

The facility also houses a fully functional drilling rig – complete with 400 ft of cased hole under the rig floor – to provide further hands-on opportunities for both rig-based personnel like drillers and for technicians. “We actually use this rig to train our electrical techs as part of our Amphion training program. They get the chance to familiarize themselves with the system and practice replacing components,” Deric Simmons, Director of Field Training & Development for the Houston Technical Support Center, said.

As hard as it is to find competent and experienced rig-based personnel, Mr Hunter said it’s often even harder to find competent and experienced equipment technicians. Besides going through a gamut of contractor and OEM training courses, they’re also taught to continuously learn from each repair that’s made. “As we repair a top drive, for example, we make improvements to it based on lessons learned,” Duane Cuku, Operations Manager for the Houston Technical Support Center, said. “We try to add value throughout the recertification cycle to eliminate the bigger problems.”

This spring, Precision sent its superintendents and operations managers to a DNV course on root-cause analysis. “For any downtime above eight hours, we’re going to do a full-blown root-cause analysis and track that data in our system,” Mr Hunter said. The details are still being worked out, but he expects the initiative to help Precision address high-frequency failures. The top drive is likely to be the first piece of equipment studied, he added.

Still, regardless of how much resources contractors invest in ensuring the integrity and reliability of their assets, they must keep in mind that rigs and equipment don’t last forever. In 2012, Precision decommissioned approximately 50 Tier-3 rigs built in the 1980s, replacing them primarily with Tier-1 newbuilds. Those older rigs lasted more than three decades, but Mr Hunter wonders if today’s newbuilds will see the same life expectancy. “The numbers don’t lie. We’re drilling wells in a third or a quarter of the time we used to. It’s going to be interesting to see the impact from unconventionals development over the next decade. Contractors will have to do more to maintain their equipment, or rigs will not live 30 years like they used to.”

Building in reliability from the start

When it comes to ensuring asset integrity for drilling equipment, NOV is adopting lessons learned from the aerospace industry. “When they send their space shuttle up, it stays. That’s the model we have to mimic because, unlike the automobile industry, we don’t have the luxury to build 150 prototypes of a top drive before it goes in the field. We simply don’t have the volumes they have in the automobile industry. Our customers are waiting on our products so they can start drilling. This means we have to get it right the first time,” NOV’s Mr Menon said.

By studying failure modes and failure mechanisms, the company is working to mitigate defects right from the beginning – in the manufacturing process. “We never send it up if we think something is going to go wrong. That’s really the way we’re building our equipment now,” he said.

As an example, back in 2006, boosting reliability for top drives primarily revolved around building in more redundancy and making sure customers could easily get a replacement part and the right service people to the right place at the right time. “But in 2014, our top drives now have vibration sensors to look at what’s going on with the gearbox and the bearings. We have monitors that look at the lubrication oil that’s going through the system to identify potential failures and make sure it doesn’t fail during operations,” he said.

Those types of sensors and technologies now collect valuable data that is sent to a real-time center where experts can monitor, for example, an increase in vibration. “We start watching it and keep the customer aware of it. We might say, ‘The next time you have an opportunity to take a break, let’s replace this part so you’re not replacing it at the worst possible moment.’ ” These types of monitoring capabilities have been added to many in-service rigs, but newer rigs under construction will have these features already built-in, Mr Menon added.

Building them in ensures the sensors are properly integrated into the equipment. “The holes are already there so you’re not sticking them on or bolting them on,” he said.

Going even a step further than these capabilities, however, is what Mr Menon called smart machines – systems that look for anomalies and send notifications to the rigs. For example, data that was collected before a seal failed is saved as a pattern. When sufficient pattern data is collected, it can help the OEM or contractor to recognize the pattern before the next failure happens. “We’re calling it the Intelligence Platform, and it’s the big piece we’re going toward by adding sensors and making a lot more use of the data we’re collecting. This next level of machine intelligence allows us to look at data that is coming in to perform the pattern recognition. The more and more data we get and the more correlation we can have from all rigs, our ability to predict failures goes up significantly.”

Looking even further into the future, Mr Menon said NOV is looking at how to leverage the technology behind Google glasses and augmented reality. “So when you walk up to a piece of equipment, you already see what’s wrong with it and what its operations have been. You don’t have to look at the gauge or sensors – all the data will be readily available for you. If you need to change the oil, it will be on the glasses that you need to change the oil,” he said, noting the technology is undergoing tests now. “It’s not been put on any rigs yet, but that’s the way we’re going.”

Good, consistent data hard to come by

As condition-based maintenance is adopted more and more throughout the drilling industry, condition data is also becoming an increasingly important component of asset management. “The biggest challenge right now is not data management by itself – the biggest challenge is getting the right data in good order and consistently,” Mr van Asten with Lloyd’s Register Energy – Drilling (LRED), said. In particular, component failure and reliability data are hard to come by. “It’s not that the industry lacks data, but it’s barely communicated, and it’s definitely not always used as much as it can be. If the drilling industry doesn’t start sharing data soon, we may miss a chance.”

He pointed to the commercial aviation industry as one example where airlines must report their data to a single organization; this group can then make the data anonymous and put it to use to benefit an entire industry. “That’s really what should happen in the drilling industry,” he said, perhaps starting with data for a particular piece of equipment – like the BOP. “Picking one of the most strategic pieces of equipment would definitely give focus,” he suggested.

Risk modeling is another technique the industry can use to help ensure integrity of the BOP system. In 2012, LRED launched a BOP risk model that addresses the decision-making process of whether a subsea BOP needs to be pulled. Soon the company will provide a web-based version of the tool. “It would allow, for example, a drilling manager to have the BOP status on his iPhone. With a password, he can log in and see the status of the BOP he’s assigned to,” Mr van Asten said.

Another aspect under development is how to tie in condition-based monitoring and condition-based maintenance to the risk model. “Instead of identifying the effects of what happens once the components in the subsea BOP have failed, it will try to identify how it’s failing,” he explained. By feeding that information into the risk model, companies can try to optimize its maintenance strategy and reduce time between wells. It can also help contractors to prioritize maintenance activities.

“If you know what’s wrong or what will fail while drilling the next section, you may be able to swap out a component now even if it hasn’t failed – but you know based on data that it will fail in the next 90 days,” he continued. Based on the calculated failure effect from the BOP risk model, the components with the highest risk-contribution can be identified. This can serve as prioritization for investment in condition-based component monitoring and maintenance.

For onshore rigs, now more and more dedicated to shale plays, the risk profile may not run quite as high as in deepwater. However, asset integrity still stands on the same three tenets of people, systems and equipment (PSE), Mr van Asten said. LRED recently launched the PSE scan, which audits for 12 factors divided among the three tenets.

“This is an overview audit that looks for contributing and integrated factors into what would denigrate the integrity of equipment, the systems in use to assure that, and the people using those systems and the equipment. It goes back to the concept that the overall operational integrity of the rig is dependent on the people, systems and equipment,” said Eric Flynn, Global Marketing Manager for LRED.

However, no matter what kind of audit is being done, whether it’s the PSE scan or any of the multitude of audits, inspections or certifications a contractor can undertake, the goal of the auditor is to help the industry become better and safer – and that’s what asset integrity is all about, Mr van Asten said. “When I go out to a rig to do an audit, I don’t want to find something wrong just because it is wrong,” he said. “I like to find things that are wrong because then it allows me to talk to the people and make things better and safer.”

Click here to read related article, Maintaining pressure key to casing integrity.

ENSCO 8500 Series is a registered trademark of Ensco.