Chesapeake drills U-turn lateral to optimize tight lease space

Horseshoe-shaped well was drilled in South Texas using conventional directional assembly

By Jessica Whiteside, Contributor

Drilling longer horizontal wells has become a common strategy for extending exposure to promising reservoirs, benefiting well economics by increasing production potential. However, tight lease boundaries can limit the feasibility of this strategy in some areas. After all, how can you drill a 10,000-ft lateral in a lease that’s only 5,000-ft wide?

Chesapeake Energy has adopted a way to circumvent such space constraints by drilling a “U-turn” horizontal well. The initial lateral makes a 180° turn to create a second lateral parallel to the first in the same formation. The resulting horseshoe shape effectively doubles the lateral length possible within the lease from a single vertical section. Chesapeake developed its first U-turn well in 2020 on a lease in the Eagle Ford Shale in South Texas. The experience was presented at the 2022 IADC/SPE International Drilling Conference in Galveston, Texas, on 10 March.

Joe Kiefner, Chesapeake’s Category Manager – Completions & Sand, said the U-turn well met production expectations – within a few percentage points of the company’s type curve for the area – and saved money, helping the company to make the most out of a small lease space in a maturing legacy field.

Calling the project highly successful, Mr Kiefner said Chesapeake has added U-turns to its portfolio of wells and identified 20 to 30 more potential U-turn locations. The company has executed on a couple of those wells and is bullish about the ability of this approach to optimize tight leases where drilling the ideal straight long lateral is not possible.

“We feel like this is not something that we should just keep internal. This is something that is better for the industry, and I think is better for our ability to utilize the space that we have,” Mr Kiefner said.

Chesapeake is not the only company to try the U-turn approach. Shell successfully drilled a horseshoe well in the Permian Basin in 2019 using a rotary steerable system. Chesapeake bills its 2020 U-turn well as the first such application in South Texas and the first using a fully conventional directional assembly, rather than a rotary steerable system.

Selecting the trajectory

Chesapeake tested the U-turn lateral strategy with its service providers as a potential tool to improve well economics and options within highly developed acreage blocks in the Eagle Ford Shale.

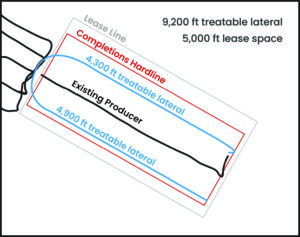

The test site was a 5,000-ft-wide lease that contained an existing producing well. The U-turn maneuver on the new well resulted in a completed lateral length of 9,200 ft (4,900 ft of treatable lateral in one arm of the U and 4,300 ft in the other). According to Chesapeake, this trajectory significantly improved well economics by “utilizing a horizontal turn as a hydrocarbon pathway, rather than an additional vertical section from a new well to gain the equivalent treatable lateral length.”

The measurement of treatable length does not include the U-turn portion of the well. To maximize the in-unit footage available for the lateral length, the company drilled the curve section into the adjacent unit and did not frac that section. Shell reportedly also elected to omit curve stimulation on its 2019 horseshoe well. Chesapeake’s case study report noted that to frac the curve would be “capitally inefficient due to the turn portion of the lateral being drilled in the direction of maximum horizontal stress, which would not optimally grow hydraulic fractures perpendicular to the wellbore.”

Planning pays off

In some cultures, the horseshoe is a symbol of good luck, but developing the horseshoe-shaped well on Chesapeake’s Eagle Ford lease took more than just luck; it took lengthy planning, modeling and simulations before drilling began. That was followed by real-time updating of factors such as torque and drag (updated at 1,000-ft intervals).

Cumulative degrees and Directional Drilling Index (DDI) values were among the key elements considered during planning and monitoring to understand the tortuosity associated with the U-shaped path. The team’s DDI assessment found many successfully drilled and completed wells with complex trajectories that had higher DDI values than what was expected for the U-turn, increasing confidence in their ability to execute the unusual path.

“If it doesn’t work on paper, it’s probably not going to work in real life. But all of our models from the drilling and completions standpoint showed that it worked on paper. It was just on us to go execute,” Mr Kiefner said.

The team used Chesapeake’s historical base model for the area to guide its expectations for the well and applied the company’s standard best practices to mitigate risks. Their due diligence included drafting contingency plans for various scenarios, including developing a backup option to continue development if the U-turn failed.

“At any point, if things went sideways, we could have stopped that plan and cased out a single 5,000-ft lateral and just drilled another vertical section,” Mr Kiefner said. “We had planned for that contingency and permitted it as such.”

Adjusting in real time

Fortunately, they didn’t need to activate that fallback option as the U-turn project went almost entirely according to plan, despite some on-the-fly adjustments required to motor and mud weights. Surprisingly, the added tortuosity of the U-turn did not have a very large impact on operations, said Riley Schultz, Drilling Engineer for Chesapeake.

“Casing went down just like we expected, within 10% of the expectations, as far as final hookloads go. It was a relatively smooth operation from the drilling side and went according to our pre-planning expectations.”

As the team monitored drilling progress, they paid close attention to the tortuosity plots – wary of the potential for excessive doglegs – and made changes as needed to meet their motor yield expectations in the turn. From an initial 7-in., 1.93° bent housing mud motor, they followed up with a 2.12° bent motor to help build the curve. After drilling 1,000 ft of the turn, the rotation required to stay on plan was deemed too high, and they switched to a 1.83° motor for the rest of the well, meeting their pre-drill expectations for rate of penetration, required weight on bit, and pressures.

The team also decided to adjust the mud weight after seeing indications of hole instability while making the turn, particularly when they got almost exactly parallel with the maximum horizontal stress. They raised the mud weight from 10 ppg to 11.3 ppg based on an area-specific, real-time mechanical earth model that showed the higher weight would maintain hole stability even while drilling in the azimuth of maximum horizontal stress.

“After we had raised the mud weight there, for the rest of the well we saw no more signs of hole instability,” Mr Schultz said, calling this mud weight lesson a big takeaway from the project and something that Chesapeake has since applied to its work on other U-turn wells.

Executing completions

On the completions side, making sure that the wireline and coil tubing was able to convey around the turn was the team’s main concern. Mr Kiefner noted they had run more than 25 wireline simulations and used several software systems to make sure everything checked out for factors such as toolstring weight and length, run-in-hole and pull-out-of-hole speeds, and friction or stretch coefficients. The subsequent completions activities went so smoothly that it even felt a little anticlimactic, he said.

“From an execution standpoint, wireline and coil tubing, there were no issues whatsoever. Anecdotally, the company (on location) said that had we not told them there was a downhole turn, they wouldn’t have known it was any different – it went that smoothly.”

The team also monitored the adjacent legacy producer throughout the project to ensure there was no adverse impact. “We didn’t see anything that caused us any level of concern from a fracking standpoint, but it’s because we planned for that and we spaced off of it accordingly,” Mr Kiefner said. DC

For more information, see IADC/SPE 208801, “Successful Planning And Implementation Of First South Texas U-Turn Lateral.”