Recovery holds steady across North America

Pipeline constraints likely to hold back growth in Permian drilling, while Bakken resurgence takes many by surprise, forecast to continue

By Rick Von Flatern, Contributor

- Rig activity in the Permian is likely to stay fairly steady over the next 18 months.

- Bakken broke production records in 2018; number of well completions there in July was highest since 2014.

- Some shale plays have reached a level of development where they will likely not require significant increases in drilling to maintain production.

- Some operators are pulling back on lateral lengths to prolong life of the well.

Predicting how the world of North American onshore drilling will look in 2019, most experts agree, requires only a look back to 2018. All the primary signals that industry analysts interpret to assess probable future drilling activity – rig count, dayrates, crude prices – show no indication of significant movement from current levels.

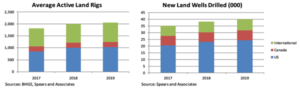

“The average rig count in 2018, we predict, will be 1,011 in the US and 208 in Canada,” said John Spears, President of Spears and Associates. “In 2019, we predict about 1,040 for the US and 211 for Canada, or about 3% overall growth.”

Similarly, Mr Spears expects WTI prices to average about $67/bbl in 2018 and move just slightly upward to average about $70/bbl in 2019. Based on a census of publicly traded contractors, Spears & Associates said dayrates increased by about 14% in Q2 2018 from Q2 2017, reaching approximately $24,000 in the US and Canada. But because the rig market has tightened and is driven by high-tech rigs, he expects overall well costs to move upward only about 5% from the end of 2018 to the end of 2019, with dayrates to follow suit, remaining in a range from 5% to 10% over the same period.

Likewise, while the firm expects 23,100 wells to be drilled in the US in 2018, it predicts that number will grow only slightly to about 24,300 in 2019. Canada, Mr Spears said, will see a similarly small increase in the number of wells drilled, from 7,300 in 2018 to about 7,400 in 2019. Because it is today the dominant onshore North American oil play and an engine of US oil production growth, the Permian Basin has an outsized influence on drilling and completion activity levels in North America.

“Our thought now is that we will see rig activity (in the Permian Basin) stay fairly steady over the next 18 months,” Mr Spears said. “And operators in the Permian Basin will slow completion work – there has been a big increase of drilled but uncompleted (DUC) wells – until pipelines come into service, and that is when completions will pick up.” Mr Spears said he expects the pipeline constraint to be resolved with added infrastructure by late 2019 or early 2020.

Predictions for limited growth in the Permian Basin is roundly shared by oil and gas analysts, including Artem Abramov, Vice President Shale Analysis at Norway-based Rystad Energy. “Our overall expectation is we might see up to 40 or 50 new rigs in the Permian in the next year compared with where we are today,” he said. “We expect a 10-12% growth in drilling activity.”

Above-Ground Constraints

A major concern for US land operators is a lack of pipeline, truck and rail capacity to carry production from the field to market. According to International Energy Agency (IEA) Analyst Olivier Lejeune, recent and rapid expansion of production in the Permian reduced the amount of available pipeline capacity to just 160,000 bbl/day in December 2017.

“This small capacity cushion is likely to come under pressure this year, despite capacity expansions of the Midland to Sealy, BridgeTex and Permian Express 3 pipelines,” Mr Lejeune wrote in a commentary for the IEA in March 2018. “Ultimately, Permian and Eagle Ford takeaway capacity is likely to become insufficient by mid-year, with a deficit possibly reaching as much as 290,000 bbl/day during the first half of 2019.”

This constraint on production creates the specter of significant price discounts for producers in these areas and has forced operators to turn their attention from growing production through drilling to profit taking. Prices paid to operators for production are often lowered, or discounted, by markets to factor in the higher cost of transporting the product from the field as a result of inadequate infrastructure. That is because, when operators continue to add production through drilling, they face the penalty costs to get it to market through a strained transport system and significant logistics issues that may render impossible any movement of oil to market.

“So operators are talking not about growing production but growing profitability,” Richard Spears, VP of Spears and Associates, said recently on the company’s podcast, The Drill Down. “Rather than drill and produce and get to market or not get to market, they may decide it makes economic sense to wait (for pipeline capacity to expand) instead of barreling ahead.

“If you make drilling activity flat with no added completion activity, you still get about 600,000-barrels production increase,” he added, “which is still 200,000 to 300,000 barrels a day above takeaway capacity.”

The upshot of such a strategy may allow operators to drill 10-20% fewer wells while still adding profitable production.

Other Plays

While heightened activity and oil production in the Permian Basin has held center stage for much of the North American land market over the past 18 months, the Bakken play in North Dakota – much to the surprise of many analysts – broke production records in 2018 amid healthy levels of activity.

“The Bakken is a basin that surprised the market because it is a much more pure liquid play,” Mr Abramov said. “Very few people thought we would see recovery of the production that we have seen there. It has made quite significant progress.”

In July, more than 150 well completions were performed in the Bakken, the highest level of activity since 2014. And operators for whom the Bakken is their core play appear committed to the basin’s development.

“Next year, activity and production growth will likely continue,” Mr Abramov said. “We do not see it slowing down until the early 2020s. The next two or three years will be very positive.”

“The Bakken is getting more attention now,” said Audun Martinsen, Partner, Oilfield Service Research at Rystad Energy. “Players in the Bakken are deploying capital and getting the count of wells up by 30% and next year by an additional 5%.”

Wood Mackenzie reports that, owing to this new interest and capital investment, North Dakota oil production reached new all-time highs in 2018, churning out 1.27 million bbl/day in July, according to the company’s most recent figures from the state.

Pablo Prudencio, US Lower 48 Upstream Analyst at Wood Mackenzie, said operators are fueling the Bakken momentum with nearly $5 billion in planned capital expenditure this year. And with lower acreage acquisition costs than the Permian and fewer risks of cost inflation and crude takeaway constraints, activity levels in the mature basin have increased in recent months.

Competitive breakeven prices in the core of the North Dakota shale plays have prompted legacy operators to ramp up production, and elevated prices are enticing some long-time Bakken and Three Forks operators to step outside of earlier prime areas of the basin. This move away from geology that yielded high-rate wells will likely prompt operators to drill more wells to maintain production.

According to a study by Connecticut-based equipment and consulting firm Concord Petroleum and Equipment Group, remaining Bakken wells with peak production of more than 1,000 bbl/day are being drained, and companies will be forced to shift their attention to drill into geology that results in peak production of just 500 bbl/day. The study indicates that operators, therefore, “may need to develop two or three times as many wells compared with current efforts in order to keep up the current production rate.”

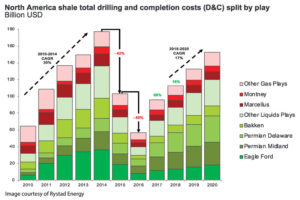

Wood Mackenzie expressed a similar conclusion, saying that the Bakken’s mature status will lead operators to spend more than $40 billion in the play over the next five years. Analysts also expect that long-term oil production growth in the Bakken will be constrained at some point by pipeline takeaway capacity and will peak at about 1.5 million bbl/day and plateau thereafter.

In Colorado, drilling activity could be scaled back at the ballot box in November, just as this issue hits the streets. Colorado Initiative 97, also called Proposition 112, would prohibit new oil and gas development from taking place within 2,500 ft of occupied buildings and “vulnerable” areas like parks and creeks. Current setbacks are 500 ft from homes and 1,000 ft from schools. Industry worries that, if enacted, the rule would eliminate 90% of drilling locations. Still, some polls show public approval for the measure at 60% or even higher.

“One thing that was clarified by the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission is that permits granted will not be affected,” Rystad’s Mr Abramov said. “Operators are getting an abnormally high number of permits to help protect them from this setback rule so that, no matter the outcome, activity in the DJ basin will remain relatively high.”

“Last week, we saw 33 permits issued, but the week before we saw 106 permits issued,” Todd J. Bush of industry analyst Energent, the North American unconventional market intelligence service by Westwood Global Energy Group, said in mid-September.

Because the increase in permits is likely driven by operators’ desire to protect themselves from the impending initiative, rather than an acceleration of drilling programs, most industry analysts believe activity in the DJ basin will remain constant. In the first half of 2017, Mr Bush said, the average rig count was around 26, with only a slight bump in the year’s second half.

“We have been essentially moving a little higher but still around 25 to 30 rigs, which is a little misleading because of pad sizes,” Mr Bush said. “Ninety-seven percent of wells drilled in the DJ basin are on pads, and those pad sizes have increased in recent quarters from four to six wells per pad to 10 to 15 wells per pad, for some operators.”

That means that even if the rig count grows only modestly in the DJ basin, the number of wells drilled may realize a greater increase. “In Q1 2018, we were tracking about 350 wells,” Mr Bush said. “In Q1 2019, we see that rise a little to 360 wells drilled, a slight quarter-to-quarter increase.”

Some DJ basin operators, like those in the Permian, are also concerned about pipeline constraints in 2019, but Mr Bush said he believes such concerns will be short-lived and drilling activity and completion activity will remain steady.

Some observers had speculated that other basin operators, particularly those in the Permian that are bumping up against pipeline and infrastructure capacity, might move operations to the DJ Basin. To date, Mr Bush said, that has not happened.

“We thought we would see further investment from the Permian to the Eagle Ford or Midcontinent but only heard of a handful of companies talking about investing in the DJ,” he said. “I don’t believe there are any companies that had specific Permian assets that are going to move back to the DJ.”

In contrast to the DJ Basin, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) suggested in an August 2018 report that Permian operators may move to the Eagle Ford in Texas in mid-2018 and in 2019. While acknowledging that the Eagle Ford covers a smaller geographic area with fewer prolific formations and fewer opportunities to drill compared with the Permian, the Eagle Ford region is not pipeline constrained.

Movement to the Eagle Ford offers operators a viable alternative while awaiting new pipeline capacity in the Permian. However, because drillers and operators have optimized drilling practices since the first wells in 2008, an influx of new operators will likely provide only modest opportunities for increased drilling activity. Activity peaked in 2014 when the Texas Railroad Commission issued 5,613 drilling permits. In 2017, the commission issued just 2,123 permits. That pace seems set to remain constant or even decline, as the commission issued just 1,574 permits in the first three quarters of 2018.

“We see that companies are becoming quite efficient in terms of drilling efficiency,” Rystad’s Mr Martinsen said. “Operators are now spending 21 days per well on average, and this compares to 28 in 2014.”

The second-largest plays behind the Permian in terms of rig activity are the South Central Oklahoma Oil Province (SCOOP) and the Sooner Trend, Anadarko Basin, Canadian and Kingfisher counties (STACK) in Oklahoma. Early in 2018, SCOOP and STACK operators experimented with denser well spacing to improve production but found the practice did not deliver hoped for results and have since reduced drilling activity slightly. “But overall well results and economics are very favorable,” Mr Abramov said. “It is not a pure oil play. It is a resource play, so you get significant uplift for your revenues from gas and natural gas liquid streams, and all (STACK AND SCOOP) players plan to continue to develop very aggressively into 2020.”

Some of the most prolific shale plays in the US are nearing a level of development that is unlikely to require significant increases in drilling activity to maintain production. For example, in the Marcellus play, referred to as the Appalachia region, US EIA figures reflect 2017 and 2018 rig counts substantially recovered from lows of 30 rigs to about 75 today, a rate that has remained steady for more than a year.

Mr Martinsen said that he expects growth in the region to be “quite muted” at about 10% over the next few years. Similar trends can be seen in the Haynesville plays, where rig counts remain far below regional peaks and where growth in drilling activity is expected as production remains strong.

More Shorter Laterals

Drilling activity in 2019 will likely be impacted not just by outside economic forces but also by impending near-term technical and logistic changes. One innovation, in particular, may indirectly increase drilling activity by convincing drillers of the advantages of drilling more but shorter horizontal laterals per well.

A recent study by Wood Mackenzie Research Director for the Lower 48 Upstream Robert Clarke highlights certain phenomena essentially driven by how operators exploit shale formations. While the industry has long known that horizontal, fractured shale wells exhibit significant decline rates early in its life, the study indicates that the pace at which production declines and a shortened well life may be related to current industry drilling and completion practices.

“We are learning that horizontal wells in general are harder to produce once they get older,” Mr Clarke said. “And that is because the laterals are so long that any issue you have with them, such as slugging or debris that may be a mile or two out from the kickoff point, is hard to clean out.”

The ultra-long reaches that have become commonplace in shale drilling also typically result in significant tortuosity issues when operators encourage drillers to geosteer wells to the landing zone in an effort to optimize reservoir-wellbore contact. When the well’s natural energy is no longer sufficient to lift fluids to the surface – the primary cause of early shale well production decline – production engineers must install artificial lift systems to capture remaining liquids.

Tortuosity makes installation of artificial lift pumps problematic. Once installed, the pumps often must operate at less than maximum efficiency because rotating speed or stroke length is inhibited by the well’s undulating profile.

Operators also may avoid reentering tortuous wellbores because the risk and cost of entering them is high. Consequently, operators often opt to perform fewer well interventions; fewer interventions and less preventive maintenance typically result in shortened well life and lower ultimate recovery.

For 2019 and beyond, Mr Clarke said, drillers may find themselves working more collaboratively with production engineers to help avoid problems associated with current drilling practices that are delivering evermore complex wells. “Drilling a 2-mile lateral may not be the optimal solution,” Mr Clarke said. “The practice isn’t as widespread as many think, and we are seeing some companies pulling back on length a bit because they want to see that the whole wellbore is appropriately stimulated, and they don’t want to leave money downhole.”

One more variable

Predicting oil industry prices and activity levels has always been a difficult endeavor due to the many unknowns. A variable unique to 2019 predictions is the state of global trade, specifically the US administration’s tariffs on imported steel. For an industry that relies heavily on the availability of steel, any increase in the cost of steel tubulars reverberates throughout the industry.

“We have seen some impact already,” Mr Abramov said. “OCTG prices have already increased because of new steel tariffs but, as of Q2 and July and August, operators have been using steel they had in stock, so no real cost inflation. Overall, steel prices are increasing, but from the operators’ side, that is offset by cost deflation on proppants and the pressure-pumping side.”

Tubulars, he added, are only about 10% of well costs and, as yet, no one has placed much significance on steel prices. For pipeline companies, however, an increase in steel prices is more important, and steel tariffs have already caused cost estimates for major new pipeline projects to be revised upwards significantly. “In the future, companies may be a little more hesitant to approve new major pipelines,” Mr Abramov said. “But everything that has been approved is moving forward regardless of new steel prices.” DC