Shale, tight gas production from Argentina’s Neuquén Basin on the rise, while Venezuela suffers dramatic production declines

Vaca Muerta expected to double 2015 production by 2018; in Venezuela, economic crisis continues to plague local oil and gas industry

By Kelli Ainsworth, Editorial Coordinator

While much of the E&P attention in Latin America is focused on Brazil’s pre-salt, Argentina and Venezuela both remain key E&P players on the continent, as well. In Argentina’s Neuquén Basin, tight gas production has already doubled since 2014, and production from the Vaca Muerta shale formation is expected to double between 2015 and 2018, according to Wood Mackenzie.

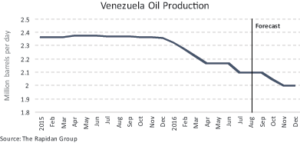

Over in Venezuela, the Orinoco heavy oil belt still has more than 200 billion barrels in proved reserves, but political and social instability are weighing heavy on investors’ minds. Production in this country has been falling slowly for more than a decade. This year, in particular, production has fallen sharply by 200,000 BPD, according to energy consulting firm the Rapidan Group. The firm is projecting that Venezuela’s production could fall another 200,000 BPD by year’s end.

Plentiful potential in Argentina

Argentina’s 6.3 million-acre Vaca Muerta, located in the Neuquén basin, may be South America’s answer to the North American shale boom. It’s estimated to hold 16.2 billion barrels of oil and 308 trillion cu ft of natural gas, according to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA). The play is still very young, with only 460 wells producing 50,000 BOED as of Q4 2015, but analysis by Wood Mackenzie shows that production is expected to double by 2018 as more projects come online. Interest has also been growing in tight gas formations elsewhere in the Neuquen Basin, said Elena Nikolova, Wood Mackenzie Research Analyst – Latin America Upstream. “The geologic potential is really undeniable,” she commented.

The country also appears to be regaining stability since President Mauricio Marci took office in December 2015. Back in 2012, the renationalization of state oil company YPF under then-president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner had made some IOCs hesitant to go all-in on Argentina. “Before there were a lot of concerns regarding capital control, exchange rates and the threat of nationalization,” Ms Nikolova said. “But with the new president in power for more than half a year now, many of these concerns have been assuaged.”

One of the first actions President Marci took was to lift currency controls, otherwise known as “el cepo” or “the clamp” in Argentina. This allowed the peso to float and once again allowed Argentinians to purchase dollars. The original goal of el cepo was to protect the government’s stock of foreign reserves. However, it also made it difficult for international companies operating in Argentina to repatriate their earnings.

President Marci has also been active in helping YPF to secure international partners to develop the Vaca Muerta. For example, in December he met with executives from both YPF and Dow Chemical. The meeting was soon followed by an announcement that the two companies would invest $500 million this year to drill for natural gas, with production expected from the Vaca Muerta’s El Orejano field. In a related statement, YPF said the field’s production could triple to 2 million cu ft/day by the end of 2016. “The government has been very active in publicizing the potential that Vaca Muerta has and showing the improvements that they’ve made so far to encourage companies to come in and invest,” Ms Nikolova said.

Chevron is one of the first major IOCs to establish a presence in the Vaca Muerta. In 2013, the company signed a deal with YPF to invest $1.6 billion in the Loma Campana block, and production began the following year. Average initial production from horizontal wells in the block has risen from 443 BOED in 2014 to 646 BOED now, according to Wood Mackenzie. As a point of comparison, the Karnes Trough in the Eagle Ford had an initial production rate of 420 BOED for its first 100 wells, which were drilled back in 2008.

The shale in Neuquén was originally developed with vertical wells, Ms Nikolva said. At the time, it was thought the thickness of the formation would yield high productivity levels even with lower-cost vertical wells. While this does lead to lower well costs and breakevens, there is also a high degree of variability in well productivity. “While the best wells do break even, because there is so much variability that does present a challenge to economics.” Since 2015, operators have been shifting to horizontal wells in the region.

Although potential in the Vaca Muerta is high, so are costs. The average cost for a horizontal well in the Loma Campana block – the most developed block in the Vaca Muerta so far – is $11.2 million. This compares with average costs between $4.9 million and $8.3 million in the major North American shale plays, according to a 2016 statistical analysis by the EIA and IHS. “One of the biggest challenges we keep hearing is the high cost of development,” Ms Nikolova said. “I think the international companies see that as the main impediment.”

One key contributor to costs in Argentina is labor. Powerful Argentinian labor unions have used their influence to require that drilling rigs be staffed with almost double the crew of a North American rig. They’ve also imposed restrictions that impact the number of hours crews can work, as well as their productivity, Ms Nikolova said. Operators in the area report, for example, that only 50% of a shift might actually be spent on productive work, according to Wood Mackenzie. There are also regular strikes and threats of strikes.

Despite these labor-related challenges, however, it’s expected that costs will eventually come down as more wells are drilled and operators become more familiar with the formation. “Like any shale play, you need to understand the reservoir, and the only way to understand the reservoir is to drill more wells,” Ms Nikolova said. “As companies continue to drill more wells, they will learn about their particular acreage.” Major operators active in the Vaca Muerta are YPF, Chevron, Total, Petrobras Argentina, Pan American Energy, ExxonMobil, Shell, Tecpetrol, Wintershall and American Energy Partners. Among these, YPF, Tecpetrol and Pan American Energy are Argentine companies.

Beyond the Vaca Muerta shale formation, tight gas formations in the Neuquén Basin are a major source of growth for Argentina’s upstream production. Tight gas production from the basin’s major producing formations – Mulichinco, Lajas, Los Molles, Punta Rosada, Basamento and Precuyo – has more than doubled since January 2014, according to Ms Nikolova. There are 11 tight developments under way in the basin, including Total’s drilling program in the Aguada Pichana block, YPF and Petrolera Pampa $150 million investment in the RincÓn del Mangrullo block, Petrobras Argentina pilot in the Rio Negro block, as well as local company Pluspetrol’s drilling program in its Centenario block.

Hastening production decline in Venezuela

Venezuela has substantial untapped reserves, particularly in the Orinoco heavy oil belt in the central part of the country. The EIA estimates the country’s overall proved reserves at 298 billion barrels, 220.5 billion of which are in the Orinoco belt. However, the country’s oil and gas production has been slowly decreasing since Hugo Chavez became president in 1999.

Then, over the past year, that production decline has accelerated rapidly due to an economic crisis precipitated by the fall in oil prices, said Fernando Ferreira, Energy Policy Analyst for the Rapidan Group. Production had averaged 3.4 million BPD as recently as 2000, but by 2015 the country was producing only an average of 2.65 million BPD. For this year, Venezuela is expected to see a year-on-year decline of 400,000 BPD.

This could be a significant blow to a country that is almost 100% reliant on oil revenues, Mr Ferreira said. But low oil prices have already made it nearly impossible for the government to pay oil and gas service companies, on top of paying for imported goods, social programs, and servicing its debt. “You can’t maintain all of them at the same time at the current oil prices. The government has prioritized debt payments,” he said.

This economic crisis has been years in the making. After Mr Chavez took office, he mandated that the state oil company, Petroleum of Venezuela (PDVSA), take ownership of all upstream projects. The taxes and royalty rates for these projects were raised, as well.

Three years later, Venezuelan workers – including PDVSA employees – attempted to force a new presidential election by going on a nearly two-month-long strike. The strike did not work, however, and Mr Chavez’s government ended up firing thousands of experienced and technically knowledgeable employees in retaliation. “PDVSA never recovered from the strike and the brain drain that happened after that,” Mr Ferreira said. This left the company with limited in-house technical capabilities to develop the Orinoco belt, he added.

Attracting foreign partners for E&P projects became even harder in 2006, when “the government passed new rules for investment and required PDVSA to be the majority shareholder in all upstream projects and joint ventures,” Mr Ferreira said.

Things have not improved since Mr Chavez passed away in 2013. The current president, Nicolás Maduro, has continued his predecessor’s policies. “At the moment, it’s a place companies are trying to leave, not go in,” Mr Ferreira said, pointing to the difficulties that PDVSA has in paying international service companies. In fact, the NOC owes nearly $2 billion to Halliburton and Schlumberger combined, he commented.

Venezuela has attempted to remedy its financial situation by appealing to its fellow OPEC members, but so far the organization has not enacted any significant measures to help stabilize the oil price. “They’ve been talking about the need to curtail production or at least find a different mechanism to support prices without curtailing production,” Mr Ferreira said. “They’ve definitely been one of the most vocal OPEC members, but we don’t expect to see any real action from OPEC other than talking up prices.”

Looking ahead, it could be another 18 months before oil prices reach a level that will allow Venezuela to both sustain its economy and invest in production increases, Mr Ferreira said. Even when prices do get to that level, Venezuela will have to compete with other Latin American countries that might offer better fiscal terms for joint venture partners. “If you’re an oil company and you’re considering where to invest, you’re going to take fiscal terms into account,” he said. “You have to look at Brazil, Mexico, Colombia and other opportunities that are going to directly compete with the projects in Venezuela.” DC