Fixing human error

‘Human behavior’ frequently cited as root cause of incidents but may not be directing corrective actions to address real cause

By Peter Bridle, consultant

Editor’s note: Peter Bridle has led HSE efforts for multiple offshore drilling companies, including Ensco, Noble, TODCO and more recently with SD Standard Drilling. He also previously worked for Shell, Halliburton and Schlumberger in various shore and field-based positions.

“So we just completed our detailed root cause analysis….”

“It took us several weeks to complete and lots of effort, but we can now most definitively say that the root cause was categorically linked to “human error.”

If this sounds like any of your own recent detailed incident analysis conclusions, then it’s likely you’ve just used up significant effort and resources without getting much in return. Simply stated, if your root cause conclusions point toward human behavior, you’re likely no further forward in either understanding the real causes of your unplanned event or in establishing an effective corrective action.

That’s because it’s hard to prevent reoccurrence for something as broad and ill-defined as human behavior. As most managers will affirm, for any corrective action to be effective, it has to be targeted and specific. This is not so easy when you’re starting off with something as vague as “human error.” Many companies do go further than this broad definition and get to specific headers such as “poor communications,” “inadequate worksite supervision” or even “a failure to follow policies and procedures.” Although these categories at first sound better defined, developing targeted and specific corrective actions based on these conclusions can prove equally challenging.

As a result, organizations – although initially appearing to move forward in the short term – will inevitably experience repeated unplanned events with similar root causes because the corrective actions failed to deliver an adequate fix. To make measured progress that can be reliably demonstrated through corrective actions that consistently hit the mark, a better understanding of human error both in terms of scale and context will be required.

Old thinking: Reacting to a few “bad apples”

Incurring a serious unplanned event – especially those carrying negative consequences, such as injuries or equipment damage – is bad news. They can hit all kinds of metrics and put a dent in business scorecards. Fortunately for most companies, serious unplanned events are a relatively rare occurrence. However, it is precisely this infrequency that not only lulls organizations into a false sense of security, but much worse, is often one of the chief culprits why organizations fail to deliver effective corrective actions.

When a serious unplanned event is incurred, it’s normally quickly reported and escalated up the food chain – driven by senior management’s stated commitment to safety. Consequently, senior management become very informed regarding how the work is executed in relation to the unplanned event.

Conversely however, they can surprisingly be much less aware of how all other work is executed, i.e., work that doesn’t demand the attention of a serious unplanned event. In other words, senior management becomes disproportionately knowledgeable regarding how a small percentage of work is executed and, through its infrequency, reassure themselves (although incorrectly) that this is not representative of how the majority of work is performed. That’s why the traditional and historic fixes put forward by organizations for unplanned events tagged with human behavior appear to make sense. If such events happen on rare occasion, then corrective actions must be targeting isolated behaviors.

However, such reasoning is based on the assumption that when people deviate from a policy or procedure, it almost invariably results in an unplanned event.

When organizations assume that procedure deviation is caused by a few “bad apples,” they’re confronted with a choice. Management then proceeds either to exercise disciplinary action or to provide more ability. Ability here can be considered as a blend of competence; skill; technical knowledge; physical capability; format, content and user friendliness of documented procedures; ergonomics; resource; fatigue, etc. In other words, a shortfall in ability can be defined as something that impairs the individual(s) from being able to execute and complete the work as they should.

Organizations often default to disciplinary action or additional training firstly because they’re easy to work with, act on and quantify. Secondly, many organizations appear reluctant to take the time to ask the more difficult and probing questions. In any event, every CEO will feel compelled to act as a means to clearly communicate the seriousness of falling short on policy and procedural compliance. Such actions, however, does nothing more than illustrate just how misinformed senior management can be in relation to how the majority of work is executed on a daily basis.

What if such behaviors weren’t the behaviors of just one or two rogue individuals? What if these behaviors weren’t isolated at all? What if such behaviors were actually a mirror image of the overall culture of entire organization?

New Thinking: Risk taking is both a systemic and motivational problem

To determine how systemic such “rogue” behaviors could be, it’s worthwhile to refer to the basic principles of risk and the sliding scale between frequency and consequence. For example, if you’re driving down the highway at 75 mph and the speed limit is 65 mph, then the frequency of this type of “speeding” behavior may need to be repeated many times before it results in an actual consequence from a traffic incident.

That’s exactly what happens when someone at the coalface is motivated to take a shortcut and deviate from a policy or procedure. If you measure only consequences, such as unplanned events, then it could be days, weeks, months or even years before anything “bad” happens that results in an actual, measurable and negative consequence.

Let’s say that someone takes a shortcut or deviates from a recognized procedure. On any particular day, the probability of a significant “negative” outcome is approximately 5%. Conversely, that means the probability of a “positive” outcome, such as saving time, money – or both – and then potentially receiving positive reinforcement can be up to 95%. For the employee, it’s a no-brainer. If the probability of being rewarded is potentially 95% versus 5% probability of something negative happening, wouldn’t we naturally expect employees to default to this type of behavior?

If someone was working at height without any fall protection secured, it’s possible that they knew full well they were supposed to have it secured but made a conscious choice not to do so. Perhaps this behavior is simply motivated to get ahead and save time, and in being aware of how their supervisor recognizes a “job well done.” For companies that have established safety management systems, years of studying “human error” in relation to unplanned events shows again and again that more than 70% of such cases are more a product of incorrect motivation rather than of ability or a direct violation. This situation is particularly hard for senior management to understand and deal with effectively. If the policy says one thing, then clearly any departure from the policy or procedure must be a violation.

Follow this logic through and discipline must be an effective corrective action. Historically, discipline and ability have been much more recognizable and straightforward. Yet, as a result, this may mean that time, resources and manpower are being wasted on corrective actions that have little or no impact on the root cause of the unplanned event.

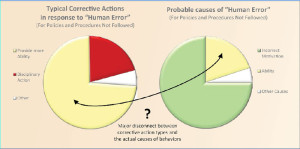

To further illustrate how problematic this thinking is, look at the corrective actions that have been developed in the past to address unplanned events labeled with “human error.” It’s very possible that the ratio of corrective actions targeting ability and/or discipline is the opposite way around – meaning that 70% or more are directed toward ability and/or discipline and much less, if any, actually target incorrect motivation (the remainder may be focused on hardware fixes). Consequently, not only have most of these historic corrective actions been targeting the wrong culprit, but the cost of this wasted effort can run into the tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars.

In the case of exercising discipline, there’s the added sting of further demotivating the workforce. Employees now end up being punished for exhibiting behaviors that just 24 hours earlier were being recognized and rewarded. The only difference being that, here, such behaviors resulted in a serious unplanned event. To the employee, however, this is interpreted as such behaviors are fine until something goes wrong. It’s not hard to see the inconsistent message and double standard being communicated.

While corrective actions that target ability and discipline are easy to relate to, think about how much more politically unpleasant (and possibly even career limiting) it would be to develop corrective actions for an unplanned event that were somehow related to – or even a product of – the overall culture of the organization. If this is really the case, it’s very unlikely that one or two employees at the coalface could directly influence the culture of the whole company. At this point, effective corrective actions have to become more directed toward the C-suite. Yet, in all my years of leading, participating and supporting detailed incident analysis, it has been a rare occurrence to develop corrective actions directly for the CEO as a result of undesired behaviors at the coalface.

Although it’s easy to develop corrective actions related to ability or discipline for one or two individuals, it’s much harder to justify more prevalent behaviors. It’s easy to say one or two individuals carried out a deliberate violation but much harder to reason that more than 70% of the workforce exhibit such behaviors. Therefore, before taking any corrective action, you have to be extremely confident you know precisely the driver for the behavior. If employees really are setting out to cause trouble, then discipline is fine. If they genuinely lack skills or technical understanding, then more ability is needed.

However, if employees are circumventing a policy or procedure based on simply trying to do a good job – which in turn is based on the incorrect motivation they’ve received from their line supervisors – then neither providing more discipline nor more ability makes sense. Remember, most organizations are full of employees (and their supervisors) who simply want to do the right thing based on the feedback they receive. Seldom are there any who deliberately set out to cause harm or trouble.

The “Fixes”

Having considered some of the basic obstacles to developing effective corrective actions, how do you make real progress with human error? How do you start to really work on its causes and prevent its reoccurrence?

Where employees at the coalface are motivated to take shortcuts, the only way to counter risk-taking behavior is to stop measuring outcomes and start increased awareness of how all work is being executed on a day-to-day basis. In short, if you’ve ever been surprised by the causes of an unplanned event, then you don’t know what’s going on. Remember, if we’ve established that the human behaviors resulting in the unplanned event are systemic rather than isolated (95% chance of positive reinforcement versus 5% chance of things going wrong), then they’ve likely been on display for all to see for some time before culminating in a serious unplanned event with “negative” consequences.

Rather than implementing simple, one-time corrective actions, such as rewriting a policy or procedure, what’s needed – at least initially – are corrective actions that fundamentally change the way safety performance is measured and rewarded. Corrective actions must be implemented to measure inputs and work execution, as well as outputs. In other words, never reward for time saving – especially when it results in coming off nonproductive time – if a shortcut was required to get there. Never punish an individual when things take longer than expected if the procedure has been strictly adhered to.

This sounds basic and straightforward, yet you might be surprised at how often middle managers misinterpret the best intentions from the corner office and focus predominantly on outputs, such as time saved or bonuses met. In other words, as long as nothing “bad” has happened today, time and money inevitably float to the top of the agenda.

These behaviors of middle managers are now so well ingrained that any genuine change or departure from this type of thinking, along with the culture that supported it, not only requires top management commitment but also direct top management engagement. If you’re really serious about changing human behaviors at the coalface, corrective actions have to change the behaviors at the C-suite.

Company leadership must be visible and promote the behaviors desired. Make clear what you want to see and then be consistent in promoting and rewarding it – regardless if an unplanned event results. The key is to become effective in measuring and responding to inputs and execution (i.e., risk) rather than waiting until something goes wrong. Inquire frequently about how work is executed to be sure that expectations are being met. Talk to middle managers regularly about expectations and inquire how they are being realized. Think about how you describe and paint a picture of “safe work” (other than no one getting hurt). Then measure how often you really promote and talk about this compared with revenue and budgets.

To summarize, if organizations desire change because they find present results unacceptable, then that change must be led. If senior management want different behaviors at the coalface, then senior management must first lead with different behaviors of their own.