Offshore, optimism for an uncertain future

Even without long-term contracts, contractors rushing to order new rigs in large quantities

By Tom Kellock, ODS-Petrodata

The last time I had the privilege of writing an article for Drilling Contractor was in March 2009, when the offshore drilling industry was reeling from the effects of the more than 70% drop in oil prices in less than a year. Today, while oil prices have recovered, although they are still considerably below the level seen in July 2008, there is still a host of unresolved issues facing both contractors and operators.

First and foremost is “Where are oil and gas prices going next?” Most observers feel that current troubles in North Africa and the Middle East, sparked by Tunisia’s revolution, are keeping prices higher than they would otherwise be. However, Japan’s reduction in energy demand due to idled refineries and factories must presumably be having a negative effect on prices, although by how much is not clear.

Longer term, the virtually inevitable slowing of nuclear power development in the United States and probably other countries, following the damage caused to a number of Japanese nuclear reactors by the March earthquake and tsunami, will almost certainly lead to increased oil and gas demand. This will be supportive of higher prices.

For US natural gas prices, the key issue is whether shale gas development will survive the environmental challenge it is now facing.

Meanwhile, the rest of the world is only in the very early stages of large-scale shale gas development, but these could conceivably lead to massive new supplies at a cost that makes offshore production an uneconomic proposition – as appears to have already happened in the United States, where jackup demand was declining rapidly even before the slowdown in the issuing of permits following the Macondo incident.

More immediately, the eagerly awaited first post-Macondo permits for deepwater drilling in the US Gulf are being issued but, as yet, with no assurance that these will come in a sufficiently steady flow to justify operators chartering rigs on a long-term basis for use in the region; any significant amount of downtime between wells would be prohibitively expensive. Meanwhile the longer-term impact of Macondo on equipment specifications and additional regulation in both the United States and the rest of the world is still by no means clear.

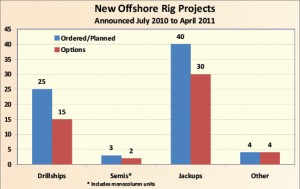

Interestingly, the reaction of many drilling contractors, both large and small, to this situation is to rush out and order new rigs in large quantities. Since the middle of 2010, no less than 72 new rig projects have been announced, and these involve options for 50 additional rigs, although there is no guarantee that many of the latter, let alone a majority, will be converted into firm orders.

The stated rationales for this new building boom vary with the rig type. For jackups, three reasons for building new rigs – at a time when less than 65% of the existing fleet is at work – are commonly given:

1. Most of the existing jackups are old and need to be replaced.

2. The work being done by jackups is technically more demanding and requires modern high-specification units.

3. Operators want new rigs for reasons of safety and efficiency even when older rigs could do the work.

There is certainly some truth in each of these statements, but at the same time they are to some extent misleading.

“Most of the existing jackups are old….” – With 202 jackups 30 years or older, there are certainly a lot of old rigs in the fleet. However, the average age of today’s rigs is 24, just under what was probably their original design life, and several 40-year-old rigs are working.

“… and need to be replaced” – It should be pointed out that age by itself does not necessarily tell you very much; many of these older rigs have gone through major refurbishment and life-extension projects. Given the costs involved, their owners clearly did not feel that these rigs needed to be replaced.

“The work being done by jackups is technically more demanding and requires modern high-specification units” – While there is no doubt that this is the case for some work today, it is not always applicable. There has been very little change in the average water depth in which jackups have been working over the past 10 years, and today few of these rigs are working in water depths greater than 300 ft. When it comes to drilling capability, it is perhaps significant that a 2008 extended-reach well, whose measured depth was a record-setting 40,320 ft, was drilled by a rig built in 1981.

“Operators want new rigs for reasons of safety and efficiency even when older rigs could do the work” – This has some validity but, at the same time, is clearly not true for all operators, who are today using more than 100 jackups 30 years old or older.

The newer, higher-specification jackups are enjoying higher utilization and dayrates than their more “lowly” brethren, but it may be rash to assume that there is unlimited scope for additional units to be added to the fleet without affecting one or both of these parameters. Given the length of time that water depths of less than 400 ft have been accessible for drilling, most prospective areas are fairly mature. With overall demand for jackups remarkably insensitive to changes in oil prices over the last decade, it appears unlikely that there will be any great increase from today’s even if oil prices stay at current levels.

The arguments listed above supporting the need for newer and more powerful jackups could be applied equally well to the mid-water floater fleet, which on average is actually older than the jackup fleet, primarily because it has not seen an influx of new rigs in the past decade.

However, with the exception of a handful of new rigs aimed at the harsh-environment markets of Norway and the Barents Sea, almost all contractors are ignoring this segment and, as far as floaters are concerned, are concentrating entirely on ultra-deepwater units. All of the recent orders and options are for rigs with a rated water depth of 10,000 ft or more.

To justify the construction of these rigs, most of which – other than the seven drillships for Petrobras – are being ordered on a speculative basis, two arguments are being put forward.

1. These rigs are available at prices that will probably never be repeated.

2. The deepwater market is where the growth in rig demand will come.

It is hard to argue with either statement. As this article was being written, Maersk Drilling just announced that it expected to pay approximately US$650 million for each of two 12,000-ft water depth drillships from Samsung, including owner-furnished equipment, project management, commissioning, startup costs and capitalized interest, i.e. everything except the cost of mobilization to the first drilling location.

This compares to almost $1 billion being paid for at least one (non-harsh environment) ultra-deepwater semisubmersible ordered in 2008.

With regard to growth in demand for these rigs, there is little doubt that, if current trends in terms of discoveries continue and oil prices do not fall below US$75/bbl for any extended length of time, many more rigs will indeed be needed. Whether they all need to be capable of drilling in 10,000 ft or even 12,000 ft of water is, however, much more debatable.

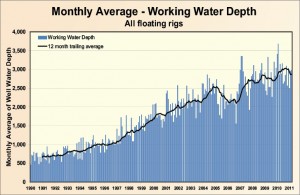

While the trend in floater use has seen a fairly steady rate of increase over the years, the average water depth in which floaters are currently drilling is only around 3,000 ft.

For the ultra-deepwater rigs, defined here as those equipped for work in water depths greater than 7,500 ft, the average well water depth has remained fairly constant over the past 10 years at a little more than 5,000 ft. Of course the number of rigs in this category has increased substantially over this period, from 17 in 2001 to 81 in April 2011, so the volume of drilling in deepwater has also increased greatly, but we are still a long way from needing many rigs to drill in more than 10,000 ft of water.

In summary, we are seeing a dynamic market with a shift in the nature of some jackup drilling, although overall demand in this segment remains fairly flat, little expected change in the use of the midwater fleet, and growing demand for deepwater rigs but perhaps not for ultra-deepwater units.

Operators should be thanking their lucky stars that drilling contractors are taking steps today to ensure that there will be enough rigs, perhaps more than enough, with the appropriate capabilities to meet their demands in the future, by ordering rigs today without, in most cases, the security of a long-term contract. Hopefully they, and the organizations involved in the financing of these units, will be well rewarded for this strategy, but undoubtedly there will be some surprises in store in the years to come.