GOM future unclear in face of Well Control Rule, falling rig count

BSEE regulations could push costs up higher even as drilling contractors struggle with budget cutbacks, multiple early rig contract terminations

By Kelli Ainsworth, Editorial Coordinator

- 60-plus rigs in US GOM have been stacked since January 2015. As of March, only five jackups were working – an all-time low.

- Industry groups, including IADC, are working to review BSEE’s final Well Control Rule. Industry remains concerned the rule will increase costs without contributing to safety and environmental gains.

- On Mexican side of Gulf, anticipation appears to be growing for country’s first auction of deepwater exploration blocks to be held in December.

Amid such cutbacks from operators, rig owners in the GOM are left competing for fewer and fewer rig contracts. “We need projects to become economically viable for our customers,” said Carsten Haagensen, Head of Strategic Account Management for Maersk Drilling. “They need to believe that the oil price at the time of delivery is at a level where it makes sense for them to go ahead with their projects and, thus, contract rigs.”

In the meantime, contractors must continue to help operators increase efficiency and bring down total well costs. “If you look at the intensive market pressures that we’re under and the new oil price reality, we need to be innovative to solve our customers’ issues with being economic,” Mr Haagensen said. “If the operators are not making their projects economic, then there is no future work for us.”

On top of tough economic conditions, drillers in the US GOM are facing new and harsher regulatory realities. On 14 April, the US Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) released the final Well Control Rule. The rule had been in the works for more than four years. It contains regulations relating to BOP systems, third-party equipment reviews, real-time monitoring, drilling margins, centralizers, inspection intervals, well design and control, casing, cementing and subsea containment. “This is a comprehensive rule containing both prescriptive and performance-based requirements that will reduce risk and save lives,” BSEE Director Brian Salerno said in a press conference announcing the final rule.

Major provisions center around the inspection, maintenance and design criteria for BOPs. For example, BOPs for deepwater rigs are being required to be equipped with double shear rams in order to reduce the possibility of a non-severable joint. In addition, third-party reviewers must certify that equipment is properly designed and fit for purpose, Mr Salerno said. The final rule also requires operators to develop a real-time monitoring plan. According to BSEE, the industry will have three months to comply with most of the rule’s requirements.

The oil and gas industry, including IADC, has expressed concerns that the rule will not achieve its intended goal of improving safety and reducing the environmental impact. Instead, it could actually have the opposite effects. Since the draft rule was released in April 2015, BSEE has received more than 5,000 pages of technical comments from 170 stakeholders, including IADC. The industry has expressed concern that some of these provisions go beyond international standards and are too prescriptive. This could result in negative impact on operations without delivering any of the safety or environmental gains BSEE hopes the rule would achieve.

Mr Salerno pointed out that BSEE did incorporate stakeholder comments where appropriate. For instance, BSEE has clarified regulation around drilling margins, allowing operators more flexibility than what was included in the proposed rule, he said. The agency also clarified its intent around real-time monitoring to make it clear that companies will have the freedom to develop a plan that best reflects their operations. “We’ve allowed for the fact that there may be alternative ways to achieve the level of safety we’ve envisioned,” Mr Salerno said. “Where appropriate, we’ve built in that flexibility.” Further, BOPs used for workovers will be required to undergo pressure tests every two weeks, which represents a change from the previous requirement for weekly inspections.

Last year, IADC and six other industry groups sent a letter to BSEE emphasizing that the cost of complying with the rule is likely to be much higher than BSEE has estimated. A cost and economic assessment performed by Blade Energy Partners and Quest Offshore, based on the proposed rule, puts the cumulative 10-year incremental cost to the industry at $32 billion. A Wood Mackenzie analysis shows that this could translate to a 55% decrease in exploration and a 35% decrease in US GOM production by 2030.

As of press time, IADC and other industry groups were still reviewing the final rule. “IADC’s subject matter experts will, over the next several days, continue to digest the technical aspects of the rule to determine its implications,” IADC President Jason McFarland said. “Our hope, of course, is that BSEE took into consideration the meticulous work of so many industry experts in composing a final rule that enables safe offshore drilling activities without imposing undue financial hardship on those who operate on the outer continental shelf.”

Record production expected

Despite a multitude of project deferments and cancellations over the past year and a half, significant production has been and will continue to come online from the US GOM over the next couple of years. Eight new projects came online in 2015, including Shell’s West Boreas and ExxonMobil’s and Anadarko’s Lucius. This year, Anadarko has already produced first oil from Heidelberg in Green Canyon. Before the end of the year, Freeport McMoRan’s Holstein Deep in Green Canyon, Shell’s Stones project in Walker Ridge and Noble Energy’s Gunflint in Mississippi Canyon are all set to begin production. For 2017, LLOG’s Son of Bluto 2 and Freeport McMoRan’s Horn Mountain Deep are on the schedule.

All of these projects will push crude production in the US GOM to record levels by the end of 2017, according to data from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA). The EIA expects GOM production to average 1.63 million bbl/day in 2016 before climbing to a record annual average of 1.79 million bbl/day in 2017. Production is expected to reach 1.91 million – a monthly record – in December 2017.

Terry Yen, Upstream Operations Research Analyst for the EIA, attributes the continuing high levels of production to the long production profiles and development periods for offshore, especially deepwater, projects. “The impact from deferred projects won’t play itself out until the mid-term,” she said. “In the near term, there are enough projects ramping up or coming online to provide the increase in production.”

To reduce costs and shorten the project life cycle, operators appear to be relying more on subsea tiebacks in the US GOM. Of eight new-field projects that came online in 2015, seven were tied back to existing production units, according to the EIA. “It’s a lot cheaper, and it gives you a shorter life cycle because you don’t have to spend years building a platform,” Dr Yen said. This trend will likely continue in 2016 and 2017, she added.

As an example of how quickly projects can be brought online when tied back to existing production facilities, Kory Kinney, Field Development Specialist focusing on North America Offshore for IHS, points to Noble Energy’s Big Bend project. The initial discovery was made in late 2012, and the field was already brought online last year. “As with any offshore project, the possibility for delays do exist. But in the US GOM, we’ve been seeing some short lead time on tiebacks,” he said.

Overall, subsea tiebacks are a tried-and-true method, Mr Kinney added. If the oil from a particular reservoir that’s being tied back to a production facility is particularly hot or acidic, special pipelines made from stronger, more corrosion-resistant alloys may be required. Overall, compared to floating production system-based field developments, subsea tiebacks present less technical challenges.

However, there are limitations to utilizing subsea tiebacks. Generally, he said, if an oil development well is more than about 15 miles away from existing infrastructure, it would not be possible to tie it back to that infrastructure. Most oil tiebacks fall in the range of 6 to 12 miles. At the same time, even if there are production facilities nearby, if those facilities are already maxed out and cannot support any additional capacity, tying back would not be an option.

Dayrates approaching breakeven levels

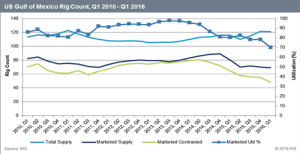

While crude production from the Gulf of Mexico is on the rise, rig counts and dayrates are moving in the opposite direction. As of March, the marketed supply of rigs in the Gulf of Mexico was at 65, according to IHS. Only 45 of those rigs were actually under contract, making for a marketed utilization rate of 69%. Those numbers reflect the fall in activity over the past year. In March 2015, there were 73 rigs being marketed in the Gulf, 61 of which were under contract.

Floating rigs are faring better than jackups, said Cinnamon Odell, Senior Rig Analyst at IHS. Marketed utilization for floating rigs has fallen by 6% over the past year, while jackup utilization is down by a whopping 35%, likely due to the shorter-term nature of their contracts. As of March, she said, there were only five jackups working in the US GOM. This is an all-time low for this jackup market.

Still, regardless of whether it’s floaters or jackups, any drilling rig rolling off a contract will be challenged trying to secure future work. “There’s a strong likelihood that they won’t get a new contract, at least not right away,” Ms Odell said. “There’s probably going to be a gap of at least several weeks or months between jobs.”

Rigs that are able to find work are earning dayrates far below what they were commanding a year ago, she added. Jackups are earning between $45,000-$68,000/day, while rates for floating rigs are as low as $150,000 for older semisubmersibles. “Our understanding is that negotiations seem to be at or near breakeven costs,” she said.

Going forward, dayrates can go down even further than that. In some cases, Ms Odell said, contractors have been willing to work for rates slightly under their breakeven costs. “Sometimes that might actually be cheaper than stacking the rig.” This is often true for rigs that will have a gap between the end of one contract and the start of another. The cost of warm-stacking the rig and retaining the crew for the next job might lead to a bigger loss for the contractor than working for a dayrate below their breakeven in between jobs.

If contracts are being renegotiated, they’re mostly of the “blend and extend” variety, where the contractor agrees to a lower rate in exchange for a longer contract term. “The operator wants to make sure that they’re saving money and the rig contractor wants to make sure they’re securing work for their rig,” she said.

In early 2016, the Gulf of Mexico saw its first rig sublet when Stone Energy sublet the Ensco 8503 semisubmersible to Apache, Ms Odell said. “Seeing that one sublet is a positive sign that there are companies out there looking for rigs,” she said. However, while subletting a rig prevents an operator from paying a hefty cancellation fee and allows the contractor to keep its rig working, the downside is that contractors are essentially having to compete with their own rigs for work. “If one rig contractor has two or three rigs they’re trying to shop and then an operator who already has one of their rigs contracted is trying to shop time on that rig, they’re effectively competing against themselves, in a way.”

The US GOM also has seen six early contract terminations since January 2015. In these cases, either the operator could not find another company to sublet their rig, or the contractor and operator were not able to come to terms during renegotiations. One recent termination came in December 2015, when Statoil canceled its contract for the Transocean Discoverer Americas drillship. The contract had been originally set to end in May 2016. Contracts have also been terminated before they even started: ConocoPhillips canceled its contract for the newbuild Ensco DS-9 drillship in July 2015. The rig’s three-year contract had been set to start in Q4 2015.

Since January 2015, 15 rigs have been warm stacked in the US GOM, while 47 have been cold stacked, according to IHS data. In the same time frame, 18 rigs have been retired from the Gulf of Mexico. So far, the retirements have occurred slowly and in small batches, Ms Odell said. “It’s a very careful balance that contractors have to strike,” she said. “It should be older rigs that are getting scrapped. But some rig contractors only have older rigs, so that makes the decision to cut rigs tougher on some contractors than on others.”

Contractors seeking smarter solutions

Drilling contractors are acutely aware of the high level of competition for work in the US GOM and, as a result, continue to seek ways to deliver additional value for operators in this cost-constrained environment.

Maersk Drilling expects drilling activity to remain low in the Gulf not just in 2016 but beyond. “We see all markets being challenged,” Mr Haagensen said. “The activity will be driven by other incentives than necessarily putting more oil through.” For example, some activity will be focused around maintaining existing operations, filling production facilities and holding onto concessions.

As of March, Maersk Drilling had two rigs, both Samsung 96K DP-3 drillships delivered in 2014, working in the Gulf of Mexico. The Maersk Viking, which began drilling for the Julia project at Walker Ridge in July 2014, is under contract with ExxonMobil until July 2017. The Maersk Valiant is under contract with Marathon Oil and ConocoPhillips, also until July 2017. The company’s third rig built for a US GOM contract, the Maersk Developer semisubmersible, has been warm-stacked following the completion of a six-year contract with Statoil in November 2015. At this time, Maersk Drilling is not building any new rigs for contracts in the Gulf of Mexico,

Under the company’s 2020 Strategy, announced in 2015, Maersk Drilling aims to develop smarter, more efficient solutions to lower total well costs for operators. “If you look at all the things our customers are facing as they go forward to produce a well, what is it that we can influence and how is it that we can help them deliver it in the most economic way, so even at today’s oil price they can make the more challenging programs work?” Mr Haagensen said. Under the strategy, the company is closely examining ways to eliminate waste from its value chain and adopt more efficient protocols for maintenance and inspection of its rigs.

Key deliverables Maersk Drilling is striving to achieve by 2020 include a zero lost time incidence rate and a financial performance within the top quartile of drilling contractors. The company would also like operators to involve them in discussions around exploration plans earlier in the process. “It very much speaks to looking at the total system cost,” Mr Haagensen said. “We’re looking at what we can influence when it comes to the costs of drilling a well, and how can we help our customers make even some of their more challenging programs work from a total cost of ownership point of view.”

Another initiative guiding Maersk Drilling’s operations, both in the Gulf and its other markets, is a cost transformation program launched in 2014. Under this program, the company seeks to lower its operational costs by 20% by the end of 2016. Maersk Drilling is working toward this goal by optimizing onshore support operations, renegotiating rates with vendors and enhancing rig crew competency. The company is also considering how its initiatives impact both their customers and their suppliers, and how cost savings could be achieved through collaboration. “We’ve been looking at how we can leverage the joint capabilities of all parties to make operations more cost effective,” Mr Haagensen said. “We’re looking at the total system cost as opposed to us optimizing Maersk Drilling’s cost, service companies optimizing theirs and operators optimizing theirs.”

The US GOM’s stability in terms of a skilled workforce and operational ease, such as spare parts availability, combined with a mature infrastructure, will help to make it more competitive and attractive ahead of other deepwater markets, Mr Haagensen said. Additionally, most of the US GOM’s operational challenges are well known. “From a deepwater point of view, we see that some projects in the US GOM will become economically viable before the more expensive assets in West Africa and Brazil.”

BSEE urges participation in near-miss program

Besides the Well Control Rule, which is likely to have wide-ranging impact on technology, equipment, economics and operations for all GOM rigs BSEE also continues to work on the SafeOCS voluntary near-miss reporting program, launched last year. The goal is to collect and analyze confidential reports of near-miss incidents in order to identify safety trends and prevent future incidents. It’s modeled on the aviation industry’s near-miss reporting system.

Doug Morris, BSEE’s Director of Offshore Regulatory Programs, characterized industry participation in the program to date as “lukewarm” and notes that BSEE has made it a priority to increase that participation. “Even in the aviation industry, it took several years to build the trust and confidence in the system, and we’re hoping that we can expedite the process within the oil and gas industry,” Mr Morris said.

To increase support for the program, BSEE has been reaching out to the industry, including meeting with trade associations such as IADC. The agency has also met with companies one-on-one to understand what is obstructing more industry participation in the program.

Overall, Mr Morris said he has seen safety improvements in the US GOM. For instance, the Safety and Environmental Management Systems (SEMS), which was finalized in 2010, has established a good baseline for safety in the industry. Prior to the rule’s implementation, only half of operators were utilizing SEMS systems voluntarily, according to data from BSEE surveys. The rule made such systems mandatory. Further, although the rule required only operators to put these systems in place, many drilling contractors and service companies have also voluntarily adopted these systems.

Mr Morris also praised industry efforts to address safety concerns through standards and best practices, precluding the need for regulations. “It’s in everybody’s best interest that the industry proactively addresses an issue,” he said. Further, BSEE sees competency and training programs, such as the ones being provided by IADC, as important factors in making the US GOM safer. “Those are the initiatives that I think are extremely helpful, especially when the industry takes a leadership position in trying to address safety concerns,” he said.

Investing in Mexico’s future

Looking southward to the Mexican GOM, there seems to be more excitement – at least more anticipation – than on the US side. An auction has been scheduled for December for Mexico’s first deepwater blocks. “A lot of companies, including the majors, are now very, very excited about the deepwater round in the Gulf of Mexico,” Duncan Wood, Director of the Mexico Institute at the Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars, said. “All the companies I speak to say it is of vital importance to them to participate in Mexico’s deepwater round.”

The first two auctions that have been held since Mexico reformed its energy sector offered shallow-water blocks. The first, which took place in July 2015, auctioned off 14 blocks in mature fields. The second, held in September that year, offered five blocks for exploration. The third auction, for onshore conventional blocks, was held in December.

There are geological similarities between the US and Mexican sides of the GOM, and many of the deepwater fields in the US GOM are believed to extend to the Mexican side. Contractors who have drilled in high-pressure, high-temperature environments and in water depths of over 10,000 ft in the US GOM – like Maersk Drilling – can certainly leverage this experience in Mexico’s deepwater market as well, Mr Haagensen said. “I think most drilling contractors will have their eye on the Mexican Gulf because of the sheer potential and the currently limited deepwater activity. It is, of course, extremely interesting to you as a contractor if you have a deepwater fleet that can operate under such operational circumstances”

Rather than discourage Mexico from holding auctions, the low price environment has actually made opening the oil market absolutely necessary, Mr Wood said. He has served as technical secretary of the Red Mexicana de Energía, a group of experts in the area of energy policy in Mexico.

PEMEX, like other oil companies, has seen its bottom line take a hit. However, budget cuts put in place by the Mexican government have resulted in the elimination of entire PEMEX business divisions. This is expected to reduce Mexico’s production capacity by approximately 100,000 bbl/day over the near term, he said. “Getting contracts issued to the private sector and getting new oil flowing out of Mexico’s resources is more important than ever before.”

The need to find partners to develop its resources may have also encouraged the Mexican government to be more inclined to listen to investor input and offer competitive contract terms than it might have been otherwise. “In a very brief 12- to 14-month window, Mexico has created an atmosphere amongst the industry that it’s a good place to invest,” Mr Wood said.

The federal government’s transparency during recent bidding rounds have been one promising sign, he added while also acknowledging that corruption remains a concern, particularly at the state and local levels. For example, there’s a risk that officials from the regulatory agencies could demand bribes from companies to secure permits.

To combat corruption, Mr Wood said the Mexican government must fully commit to implementing its justice reform, Mr Wood said. The reform, which was officially passed in 2008, is set to be implemented in June this year. “Although they will officially meet that deadline, the real story is that it will be an incomplete implementation across the country,” he commented. One of the main components of the reform is a shift to adversarial trial procedures. Prior to the reform, judges were charged with investigating the facts of a case and then rendering the decision. The new system will require each party to a case to gather and present its own evidence in open court, in front of an impartial judge.

The justice reform is expected to make it easier for the government to prosecute corrupt officials by introducing greater transparency into the country’s legal system. Judicial decisions will have to take place in the open courtroom, rather than behind closed doors, where officials could easily bribe the judges in order to escape prosecution. However, full implementation will take time, possibly as much as a decade, Mr Wood said.

Another challenge for the energy industry will be working with local authorities and communities to achieve the necessary improvements to infrastructure, such as rig yards, roads and ports. Demonstrations by local communities are not uncommon as attempts to block projects, particularly if local citizens believe they are not getting any benefits, Mr Wood said. “Local communities, when they see a new project being built, often protest against it as a negotiating tool to try and get more benefits for themselves.” This mean companies wanting to work in Mexico will have to find ways to build local support. One way to do this, he said, is to utilize local content above and beyond the minimum threshold set by the government.

The private sector and the Mexican government will need to cooperate to train the local workforce on state-of-the-art drilling and completions technologies, Mr Wood said. This could prove challenging as there is no equivalent to the community college model in Mexico, which has been a useful mechanism for training crew in the US. “I think that energy companies coming in will have to bring in their international experience on this issue and find reliable local partners at local universities,” he said.

In order to preserve contractor and operator enthusiasm for its deepwater auction, Mr Wood said, the Mexican government must stick to its established timeline and hold the auction in December, rather than hold out for a higher oil price environment. He noted that operators allocated resources in their 2016 budgets to bid on the deepwater resources, but they may not be able to keep those resources available should the auction be delayed. “It’s important to keep the momentum going on the energy reform, just to make sure that companies stay focused on Mexico.” DC